Performances

Handel and Haydn Society takes the path less chosen with Christmas program

“Well, Franklin,” Theodore Roosevelt quipped to his cousin after the younger […]

Boston Cecilia celebrates its patron saint with a feast of varied music

Celebrating a birthday around the holidays can be a tricky proposition. […]

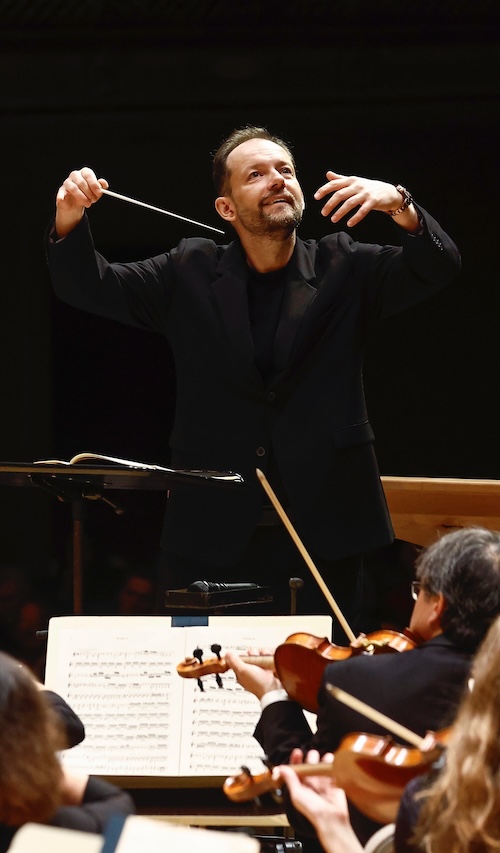

Star soloists, Boston Philharmonic soar in Verdi’s Requiem

Verdi was an opera composer at his core and his Messa […]

Articles

Critic’s Choice

Music by Mahler, Loeffler, Koechlin, Saint-Saëns and Beach. Boston Symphony Chamber […]

The Year in Review

Top Ten Performances of 2025

1. Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Die tote Stadt. Andris Nelsons/Boston Symphony Orchestra

Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra continued their streak of impressive operas-in-concert with January’s powerfully sung, iridescently played ensemble premiere of Korngold’s Hitchcockian gem. Christine Goerke’s role-debut as Marie was rightly captivating, but just as ear-catching—and maybe even more notable—was David Butt Philip’s appearance as Paul. A late fill-in for an indisposed Brandon Jovanovich, Philip turned one of the most demanding parts in the canon into a picture of freshness, vitality, and hope.

2. Mahler: Symphony No. 2. Benjamin Zander/Boston Philharmonic Orchestra

Benjamin Zander and the BPO have been spoiling Boston audiences with great Mahler performances for so long that it might be tempting to take their work for granted. But that would be a mistake, as April’s presentation of the Resurrection Symphony reminded. This performance, which included contributions from soprano Miah Persson, mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly, and Chorus pro Musica, was something special—even without the impromptu pre-concert appearance from the composer’s granddaughter, Marina. Fervent, locked-in, utterly natural, theirs was a singularly gripping Mahler Second, one that viscerally aimed to transcend the here and now.

3. Bach: Complete Cello Suites. Yo-Yo Ma. Celebrity Series

How does the world’s most famous cellist celebrate his 70th birthday? Maybe with several thousand of his closest friends at Symphony Hall and, by simulcast, across the Commonwealth? So it happened that Ma offered Bach’s six Cello Suites in a single concert—and capped off the night with an encore that brought Boston Mayor Michelle Wu to the stage as his accompanist. The spoken efforts to fuse artistry with social action didn’t always land, but no matter: Ma’s music-making was one-of-a-kind—thoughtful, probing, intimate, deeply affecting.

A duo-piano appearance of Vikingur Ólafsson and Yuja Wang was more a meeting of well-matched and brilliant musical minds than anything else. Their program was all about opposites finding common ground: Conlon Nancarrow and Rachmaninoff, Luciano Berio and Schubert, Arvo Pärt and John Adams. The riches they uncovered were never less than riveting, often exhilarating, and—as their parade of encores hinted at—potentially inexhaustible.

5. Music by Haydn, Mendelssohn, Webern, and Shostakovich. Viano Quartet. Celebrity Series.

Talk about a debut: filling in on short notice for the quartet Meta4, the Vianos showed up at Groton Hill Music with a standard program in tow—and proceeded to play the daylights out of it. Theirs were outstanding performances in every way, capped with a knockout account of Shostakovich’s knotty String Quartet No. 9.

6. Music by Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann. Julia Fischer & Jan Lisiecki. Celebrity Series

Technical accomplishment and musical understanding are adjectives that apply equally well to Julia Fischer and Jan Lisiecki, so it’s no surprise that their joint recital at Jordan Hall was so polished and colorful. Especially captivating, though, was the sheer verve with which they imbued their fare, especially Schumann’s usually unforgiving Violin Sonata No. 2. On this outing, the composer’s judgement—he always held a high opinion of this particular work—was fully vindicated.

Daniil Trifonov performed concertos of Ravel and Saint-Saëns with the Orchestre National de France Friday night in Worcester. Photo: Dario Acosta

Two weeks after playing Schubert at Jordan Hall, Daniil Trifonov was back in Massachusetts, this time headlining the Orchestre National de France’s appearance at Worcester’s Mechanics Hall. In concertos by Saint-Saëns and Ravel, he didn’t disappoint. Neither, in music by Elsa Barraine and more Ravel, did the ensemble and conductor Cristian Măcelaru—who, for good measure, capped the night with the year’s most generous encore: Bolèro.

Nathalie Stutzmann made her podium debut conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra Thursday night at Symphony Hall. Photo: Robert Torres/BSO

Nathalie Stutzmann’s conducting debut with the BSO brought together music by three composers that the orchestra, historically, takes special pride in playing. She presided over bracing readings of all of them. The Beethoven Violin Concerto featured Eberle (also in her ensemble debut) playing new cadenzas by Jörg Widmann; even without those, the German violinist’s attentive way with the line and miraculous intonation were remarkable. Alborada del Gracioso and the 1919 Suite from The Firebird offered irresistible fireworks of their own.

Edgar Meyer, Tessa Lark and Joshua Roman performed Friday night at Sanders Theatre for the Celebrity Series. Photo: Robert Torres

9. Music by Edgar Meyer. Tessa Lark, Joshua Roman, Edgar Meyer. Celebrity Series

Edgar Meyer doesn’t waste time on fancy titles: instead, he pours all his creativity into his music. This concert at Sanders Theatre, which paired two of Meyer’s string trios from the 1980s with one from 2024 plus a couple of numbers by J. S. Bach, beautifully and thrillingly straddled the line between high-art and vernacular music.

10. Shostakovich: Symphony No. 11. Andris Nelsons/Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The Eleventh doesn’t usually rank in the top tier of Shostakovich symphonies. Yet April’s performance from Nelsons and the BSO was a revelation: turbulent, spacious, focused, inexorable. On this night, the music’s expressive ambiguity held full sway, suggesting seemingly endless depths yet to be plumbed.

Honorable Mentions

The Handel and Haydn Society masterfully highlighted the drama and subtle details of Handel’s rarely heard cantatas Delirio amoroso and Tra le fiamme, with the beautiful, nuanced singing of soprano Joélle Harvey. (Lani Lee)

Fresh and faithful performances of Brahms’s music shone with Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra in the Symphony No. 1, combined with the thrilling playing of soloist Alessandro Deljavan in the Piano Concerto No. 2. (Lani Lee)

A Tie for Best Premiere

Gabriela Ortiz’s Revolución diamantina is a kaleidoscopic score of kinetic colors, textures, and rhythms that almost needs to be experienced live to be believed (especially the climactic samba). Yet, at its core, this is music of great beauty and heart. In its Boston Symphony premiere in February, led by Giancarlo Guerrero, the ballet, with its dramaturgy rooted in Mexico’s “glitter revolution,” proved illuminating both on its own terms and in how it shined fresh perspectives on the night’s canonic items.

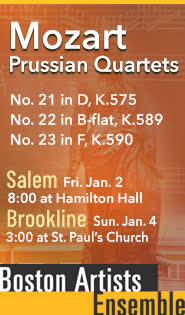

Any chamber music for a trio that involves the harp will likely court comparisons with Debussy’s Sonata for flute, viola, and that instrument. So hats off to Scott Wheeler for his well-crafted Insomnia Flowers, an enchanting, virtuosic essay for violin, cello, and harp. Commissioned and debuted by the Boston Artists Ensemble, Wheeler’s score inhabits a world all its own and, in the process, manages to make one forget just how rare this combination of instruments (or thereabout) actually is.

A Necessary Canonic Festival

Given how much Beethoven Andris Nelsons and the BSO play, January’s cycle of the full symphonies looked, on paper, a bit superfluous. Yet, in practice, the fête ended up offering real musical rewards and helped to serve as a kind of reset for the orchestra and its music director, who, in recent seasons, have sometimes seemed at cross-purposes, especially in the standard Germanic canon. And it worked: 2025 ended up as the most consistently satisfying year for the pairing since the pandemic upended life five years ago.

A Most Welcome Revival

Outside of the Cello Concerto and Enigma Variations, Elgar’s music has not fared particularly well in Boston. Perhaps that’s changing: Frank Peter Zimmermann’s account of the Violin Concerto with the BSO was the second to be heard at Symphony Hall in just eighteen months. Whether or not that trend continues, this was a concert that offered sublime, Edwardian warmth—plus the revelation that Dima Slobodeniouk is a fine Elgar conductor.

A Pair of Sixes

Not all Sixth Symphonies are created equally. But, at least since Tchaikovsky’s Pathètique, they’ve tended to be more special than not, as a pair of performances in the year’s first half demonstrated.

In March, Benjamin Zander led the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra in Mahler’s gargantuan Sixth Symphony in A minor. That this epic isn’t normally the domain of teenagers hardly mattered: the group infused their playing with a sense of purpose and confidence that belied both their youth and the symphony’s tragic cast.

A few weeks later, Andris Nelsons and the BSO assayed Shostakovich’s far more enigmatic Sixth. This is music that doesn’t give up its Great Terror-era secrets easily. Yet conductor and orchestra found a persuasive way through the score’s maze of devastation by teasing out its sense of irony and humor. “Against the assault of laughter,” Mark Twain once observed, “nothing can stand.” Shostakovich, as this night demonstrated, intuited as much—and then some.

The Kids are (Mostly) Alright

As usual, a steady flow of young and/or up-and-coming talent graced Boston-area stages this year. For the most part, they left one hopeful for the future of the art form. Mezzo-soprano J’Nai Bridges and baritone Dashon Burton continued to remind why they’re among the day’s in-demand artists. Leland Ko delivered an excellent account of William Walton’s shamefully underrated Cello Concerto.

Meantime, pianist Seong-Jin Cho presented Ravel’s complete piano works in a single, marathon recital in February and Yunchan Lim offered Bach’s Goldberg Variations in October. There was much to admire in both appearances—as well as welcome reminders that these preternaturally gifted young artists (30 and 21, respectively, at the times of their concerts) are indeed human and haven’t yet reached their ceilings as interpreters.

At the other end of the spectrum was violinist Ray Chen, whose BSO debut, alongside that of Burton and conductor Teddy Abrams, was notable more for his hammy encore introduction (beginning with a Michael Buffer-worthy “Thank you, Boston!”) than for its breathless, insistent take on Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto.

Closing Chord

Though he had been effectively retired for most of the last decade, Christoph von Dohnányi, who died at 95 on September 6, was, for more than thirty years, a regular presence at Symphony Hall and Tanglewood. Between 1984 and 2015 he led nearly 100 performances with the Boston Symphony and/or The Cleveland Orchestra (he was music director of the latter from 1984 to 2002).

The grandson of the composer Ernst von Dohnányi, son of the anti-Nazi jurist Hans von Dohnányi, and nephew of the dissident theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dohnányi brought an exactitude to his music making that reflected his storied pedigree. At its frequent best, however, that meticulousness resulted in performances—and a considerable discography—of singular freshness and spontaneity.

Posted in Articles

No Comments

Calendar

December 21

Handel & Haydn Society

Scott Allen Jarrett, conductor

Graupner: […]

News

Boston Classical Review wants you!

Boston Classical Review is looking for concert reviewers based in […]