Performances

Boston Cecilia celebrates 150 years in style with Bach and Handel gems

Longevity in a performing organization is often guaranteed by championing new […]

Pianist Fujita shows mastery, versatility in Vivo recital debut

Already established as a fine interpreter of Classical and Romantic repertoire […]

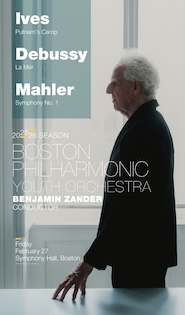

Zander leads Boston Philharmonic in stylish Mozart and noble Bruckner

One might not guess it from this weekend’s concerts at Symphony […]

Articles

Top Ten Performances of 2025

1. Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Die tote Stadt. Andris Nelsons/Boston Symphony Orchestra […]

Concert review

Adès returns to lead Boston Symphony in a vibrant season highlight

Thomas Adès conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra in music of Beethoven and Adès Thursday night. Photo: Winslow Townson

Talk about a strong finish: while the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s spring season runs through May, the ensemble’s two-month streak of concerts showcasing major new and unfamiliar repertoire that began in January comes to an end this week.

But it goes out on a high note, courtesy of composer-conductor Thomas Adès, who returned to Symphony Hall on Thursday night for his first local stand in more than two years. As is typical for programs curated by the BSO’s former artistic partner, the event featured a pair of major works of his—Aquifer and Concentric Paths—plus something from the standard canon, on this occasion Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6.

And who would have guessed that the 200-plus-year-old warhorse would come out sounding as fresh as the evening’s 21st-century items? That it did owed as much to Adès’ vibrant relationship with the BSO as to the British musician’s fresh, idiomatic conception of this “Pastoral” symphony.

Thursday’s Beethoven hardly reinvented the wheel. Its tempos were purposeful, but within the mean for standard performance practice. Adès periodically drew out a rustic rawness from the violins—the first movement had a bracing edge, with some bent notes at the beginning of the storm section, and there was no shortage of open E strings in the finale. Yet his larger approach was never sidetracked by the score’s picturesque effects.

Instead, Adès paid close attention to issues of dynamics, balance, and style. This was a richly textured Sixth, with a multidimensional, almost physical, quality to the symphony’s opening half, especially its depiction of a brook. Granted, the latter may have suggested a river rather than a stream, but no matter: the depth of the music’s inventiveness and the excellence of the BSO’s playing—the woodwinds, in particular, were outstanding across the evening—carried all before it.

In this Sixth, the intensity of the orchestra’s delivery in quiet passages consistently impressed, as did their control over explosive spots. The first timpani thwack during the thunderstorm, for instance, was like an electric jolt. But the ensemble’s lucid illumination of that section’s later rhythmic thickets was equally stirring.

A similar textural focus paid dividends in the finale, whose hymn-like refrain unfolded radiantly. Here as elsewhere in the symphony, Adès and the BSO drew out the music’s play of variation and dance with clarity and purpose.

Those latter qualities also marked the evening’s rendition of Concentric Paths, Adès’ 2005 concerto for violin and orchestra. Ambivalent though the composer may be about writing in standard genres, this 20-minute effort occupies ground that is both firmly traditional and decidedly its own.

Its three sections follow a familiar fast-slow-fast pattern, with the middle one sounding, over its first half, a bit like an angry deconstruction of Bach’s famous chaconne. The finale channels folk song and, in some of its off-kilter rhythms, Sibelius. Throughout, the violin writing is acrobatic and frequently stratospheric.

Augustin Hadelich was the violin soloist in Thomas Adès’ Concentric Paths Thursday night. Photo: Winslow Townson

Daunting though the score may be, it proved child’s play for Thursday’s soloist, Augustin Hadelich. Playing with impeccable precision and outstanding projection, the Italian-born fiddler imbued even the knottiest passagework with an inviting sense of direction and musicality.

Hadelich’s intonation was rightly breathtaking—the concerto’s high-lying noodling and melodic writing were spotlessly in tune—yet it was his grasp of the score’s shifting characters that really elevated the night’s reading. The central “Paths” movement involved a gripping play of tension and release while the finale’s spiraling transformations were dispatched with devilish glee. Afterwards, the violinist offered Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s Louisiana Blues Strut “A Cakewalk” as an encore.

For his part, Adès drew an accompaniment from the BSO that was rhythmically secure, well-balanced, and brimming with color.

Composer-conductor and orchestra were on equally firm footing in the night’s opener, Aquifer. Premiered last year by Simon Rattle and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, this 17-minute curtain-raiser analogizes the natural phenomenon of water under pressure in underground reservoirs. Roiling, dense, and unpredictable, the music is also lyrical, kaleidoscopic, and more than a little bit cheeky: the image of Wagner holding forth in a speakeasy comes to mind more than once in the course of its peregrinations and the work ends on, of all things, a blazing C-major triad.

While Thursday’s account was, perhaps, a shade blunter than not, Aquifer’s outer parts danced and its introspective spots proved hypnotic. Throughout, the BSO took to the music like the playground that it is, limning Adès’ extraordinary command of orchestral colors and textures with warmth, soul, exuberance, and wit.

The program will be repeated 1:30 p.m. Friday and 8 p.m. Saturday at Symphony Hall. bso.org

Posted in Performances

No Comments

Calendar

February 27

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Thomas Adès, conductor

Augustin Hadelich, violinist […]

News

Boston Classical Review wants you!

Boston Classical Review is looking for concert reviewers based in […]