Top Ten Performances of 2023

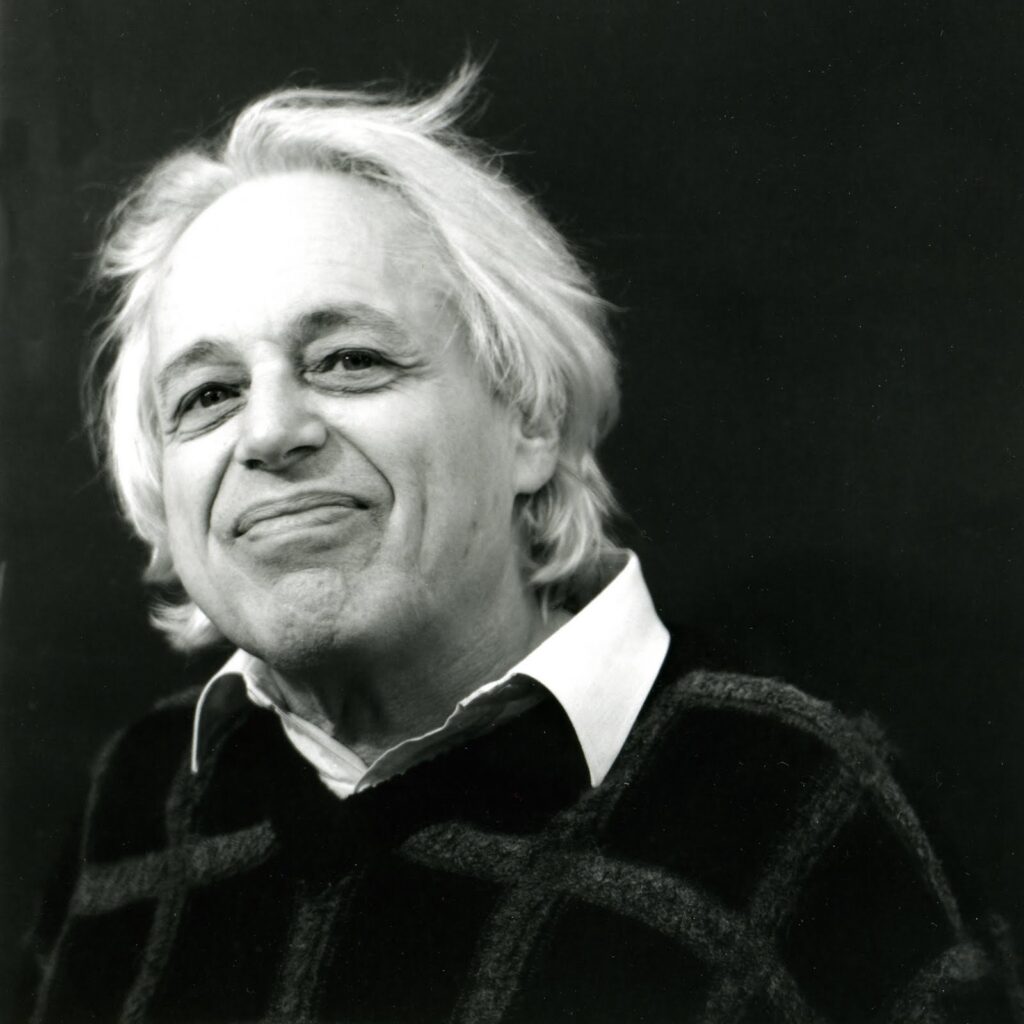

1. Sir András Schiff playing Bach, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Mozart

Sir András Schiff’s Celebrity Series recital in November was part trip down memory lane, part celebration of all things related to J. S. Bach. But above all, his survey of “very great music” from the 18th and 19th centuries (because, as Schiff put it, “Life is too short for not-very-good music”) was a demonstration of an artist at the height of his powers. Recitals of 150 minutes in Jordan Hall don’t often feel like they’ve ended too soon. This one—enchanting, entertaining, revelatory—did.

2. Music of Kodály, Tchaikovsky, and Schubert. Joana Mallwitz/Boston Symphony Orchestra

It’s not every season that the BSO get to claim a brilliant American debut. This year was an exception with Joana Mallwitz’s first concerts on these shores. The German conductor brought with her more than the usual hype from across the pond but she proceeded to live up to every word of it, leading a towering performance of Schubert’s “Great” C-major Symphony as well as some zesty Kodály and, in partnership with the equally impressive Anna Vinnitskaya, a ferocious, kinetic Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1.

3. Danish String Quartet playing Haydn, Shostakovich, Britten, and Nordic folk music

“There are only two kinds of music,” Duke Ellington once opined. “The good kind and the other kind.” The Danish String Quartet’s January appearance bore out his dictum with terrific accounts of canonic works, followed by an absorbing survey of (mostly) Nordic folk tunes, and culminating in a time-stopping encore of “Can’t Help Falling in Love With You.” What was more impressive: how well all this disparate music functioned together as a program or the astonishing rapport of the musicians onstage? Thankfully, we don’t need to choose.

4. Igor Levit playing Beethoven

Levit is a musician whose offbeat ideas sometimes get the better of him. But on this night, in which the pianist tackled the last three Beethoven piano sonatas in succession, he was firmly in his element. For flexibility, balance, and sweep, his were extraordinary, lucid, eminently “right” interpretations of these pillars of the keyboard repertoire.

5. Music of Stravinsky and Adès. Thomas Adès/Boston Symphony Orchestra

The BSO’s long relationship with composer-conductor-pianist Thomas Adès is the artistic equivalent of a legacy that keeps paying dividends. Both of his appearances in town this year were memorable, but the finest came in March, when Adès paired Stravinsky’s rarely-heard Perséphone with the local premieres of the “Inferno” and “Paradiso” sections from his new ballet Dante. An homage to that author’s Divine Comedy as well as to Franz Liszt, the latter score proved as irresistibly fresh, inventive, and dazzling as any Adès has written—and an electrifying reminder of how invigorating and vital contemporary music can be.

6. Handel’s Israel in Egypt. Jonathan Cohen/Handel & Haydn Society

The Jonathan Cohen era at the Handel & Haydn Society began in style in October with a performance of Handel’s 1739 oratorio depicting the biblical Exodus from Egypt. The performance was thrilling both chorally and instrumentally and the soloists—drawn entirely from the company’s ranks—largely impressed. Taken together, the occasion marked an auspicious new beginning for the venerable 208-year-old group.

Benjamin Zander conducted the Boston Philharmonic in Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with soloist Sarah Connolly. Photo: Hilary Scott

7. Music of Schubert and Mahler. Benjamin Zander/Boston Philharmonic Orchestra

Mahler’s symphonies are no stranger to Symphony Hall. But his song cycle Das Lied von der Erde is: the Boston Symphony has only presented the work twice this century (and not since 2013). The Boston Philharmonic last assayed the score even further back, in 2004. Accordingly, the ensemble’s April concert, which paired Das Lied with Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, promised to be an event. It proved as much, with Benjamin Zander leading a reading that was, by turns, winsome, reflective, and, in Sarah Connolly’s touching delivery of the concluding “Der Abschied,” evincing Zen-like poise and focus.

8. Ligeti 100. New England Conservatory of Music.

By all accounts, György Ligeti had a memorable residency at New England Conservatory in 1993. It was fitting, then, that students and ensembles from NEC presented such engaging performances of some of the Hungarian maverick’s hits as part of the BSO’s weeklong celebration of the composer’s centenary in November. The evening’s selections–highlighted by a bracing account of the Chamber Concerto and a rare outing for the riotous, gleefully anarchic Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures–sounded fresh, unpredictable, and zany as ever. One could only imagine that the exacting Ligeti, had he lived to see the day, would have loved every second of it.

9. Joshua Bell & Daniil Trifonov playing Beethoven, Prokofiev, Bloch, and Franck

The Celebrity Series’ emphasis on “blockbuster recitals” sometimes hits, sometimes misses. This time around, the combination of two of the most electrifying instrumentalists of our day triumphed from the start. There was dynamic Beethoven, haunting Prokofiev, soaring Bloch, and, to crown the night, a galvanic performance of Franck’s A-major Violin Sonata that simply had to be heard to be believed.

10. Music of Bartók, Bunch, Biber, Price, and Wiancko. Earl Lee/Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra

Boston Symphony assistant conductor Earl Lee made a terrific impression in this concise and wonderfully varied program of music for strings. Leading Pro Arte, he drew lean, limber performances of dance-themed works written across three-and-a-half centuries that made, for a brief spell on a beautiful spring afternoon, the concept of time superfluous.

Honorable Mentions

The BSO’s second program of the new year featured the Symphony Hall debut of conductor Karina Canellakis, whose command of demanding, relatively unfamiliar repertoire (Dvořák’s late tone poem The Wood Dove and Witold Lutoslawski’s Concerto for Orchestra) was as impressive as her ability to draw out playing of real delicacy and nuance from the orchestra. Add to this the fireworks Nicola Benedetti brought to her account of Karol Szymanowski’s Violin Concerto No. 2 and we had the makings of an ideal night at the symphony.

BSO music director Andris Nelsons has led a number of impressive presentations of operas-in-concert during his tenure. This time the offering was partial: the Overture and Venusberg Music, plus Act 3, of Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Even so, the singing (Klaus Florian Vogt in the title role, Amber Wagner as Elisabeth, and Christian Gerhaher as an unforgettable Wolfram) was splendid and the orchestral playing burnished. One left Symphony Hall hoping Nelsons might someday lead the whole of this incomparably rich and tuneful Wagnerian effort in Boston.

Frank Bridge is a composer whose output has been almost entirely overshadowed by his reputation as Benjamin Britten’s teacher. So it was particularly welcome to hear Benjamin Grosvenor and the Dorics team up for a thrilling, altogether compelling performance of Bridge’s Piano Quintet in April. Like the Haydn and Beethoven quartets with which it was paired, this is music of real personality, style, and immediacy–a brilliant showcase of the composer’s voice, as well as a perfect vehicle for the extraordinary musicians who brought his score to life.

The BPYO’s eleventh season was, atypically, devoid of guest instrumental soloists. Instead, its programs mined (with the exception of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in May) the purely orchestral canon and nowhere more impressively than on this March outing of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5. A virtuoso workout by any measure, both pieces were dispatched with a confidence, brio, and professionalism that, as often is the case with this ensemble, belied the youth and presumed inexperience of the players.

Endings, Anniversaries, and a New Beginning

2023 saw the disbandment after 47 years of the Emerson String Quartet, who gave their final Boston concert in January, as well as the deaths of composers Kaija Saariaho and David Del Tredici, pianist Menahem Pressler, and New England Conservatory icons Russell Sherman and John Heiss.

For several prominent local ensembles and organizations, it was also a year of celebration.

Odyssey Opera marked its tenth birthday while, in October, the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra opened its 45th season and the Celebrity Series its 85th. Meantime, Boston Baroque and Collage New Music concluded their respective semicentennials in the spring.

A smaller anniversary, but notable, came in the fall when Andris Nelsons began his tenth season as the BSO’s music director. He’s in august company: the only other conductors to accomplish that feat were Wilhelm Gericke (over two separate appointments), Serge Koussevitzky, Charles Munch, and Seiji Ozawa. A decade on, Nelsons seems to have settled comfortably into his job, even as unbalanced orchestral playing and interpretive unevenness have increasingly become hallmarks of his appearances.

For a partnership that’s brimming with potential–and consistently exhibiting purpose and energy–one need only look to the Handel & Haydn Society which, as noted above, began a new chapter in October with the start of Jonathan Cohen’s tenure as artistic director.

The two programs he’s led thus far, both of oratorios by Handel, confirmed the wisdom of his selection: neither performance wanted for drama, vigor, or electricity. One looks forward to Cohen carrying this spirit into the purely instrumental realm (we’ll get a little bit of that in his March visit), but he’s already ensured that the country’s oldest performing arts ensemble is the picture of musical vitality.

Opera here, there, and everywhere

Some years it feels like Boston is a place where opera companies come to aimlessly wander the city’s cow paths. Not in 2023, though, thanks to some good luck as well as smart creative and repertoire choices.

Maybe the most conspicuous stroke of fortune came in May, when Boston Lyric Opera’s presentation of Rhiannon Giddens’ and Michael Abels’ Omar coincided with the announcement that the score had won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Music.

Later in the year, the company’s efforts at social relevance led it to continue its series of revisionist productions of operas by Giacomo Puccini. This fall’s well-intentioned but sometimes clunky update of Madama Butterfly attempted to address that work’s checkered dramaturgical history by updating the action to 1940s California and an Arizona internment camp, while also tweaking key aspects of its plot. Despite its hiccups, the adaptation was well-cast, -sung, and -played

BLO is usually on stronger footing with its less-interventionist presentations in non-traditional venues. Indeed, they struck gold in March with a double-bill of Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle and four songs by Alma Mahler at The Terminal @Flynn Cruiseport in South Boston. Naomi Louisa O’Connell and Ryan McKinney offered gripping portrayals of Bartók’s doomed couple and David Angus led a reduced BLO orchestra with security and refinement.

Elsewhere around town, Odyssey Opera’s presence was limited to a single night in ’23, but their February production of Tobias Picker and Aryeh Lev Stollman’s Awakenings hauntingly raised big questions while not settling for easy answers.

Meanwhile, Boston Baroque gave Christoph Willibald Gluck’s infrequently performed Iphigénie en Tauride a hearing in April. Though the venue–GBH’s Calderwood Hall–was unideal, the economical staging, excellent instrumental contributions, and wonderful singing (highlighted by soprano Soula Parassidis’ focused account of the title role) were invigorating.

Likewise refreshing was White Snake Projects’ September offering of Monkey, a Kung Fu Puppet Parable. True, the libretto and score weren’t flawless. But they were entertaining and the larger work somehow managed to deftly weave into one singing, puppetry, martial arts, video projections, and references to various cultural totems (The Wizard of Oz, ‘70s and ‘80s action TV shows) one doesn’t normally encounter in the opera house.

An Excellent New Hall

Boston’s a place where, as poet David McCord once put it, “the past is physically as well as traditionally a part of…modern life.” That’s emphatically true of the city’s big concert halls and venues, which have histories as storied as their edifices are imposing and seating usually uncomfortable.

More recent (and smaller) spaces, like Longy’s Pickman Hall, have winning acoustics, if not commensurate aesthetic appeal. The Gardner Museum’s Calderwood Hall excepted, one has to head a bit farther afield to find both of those things, either to Rockport’s gorgeous Shalin Liu Performance Center or, now, to Groton Hill Music Center’s astonishing Meadow Hall.

The latter opened a year ago and, this season, the Celebrity Series is presenting four recitals there. I attended the first, in October, and the venue proved a find. It’s bright, airy, without a dead or dry spot–and this in addition to excellent sight lines and ample parking. What’s more, the experience cemented what photos of the hall had been suggesting for months already: in just about every way, the place is a gem.

Posted in Articles