Pianist Hamelin meditates engagingly in Celebrity Series recital

Pianist Marc-André Hamelin performed a recital Sunday afternoon at Jordan Hall for the Celebrity Series of Boston.

Marc-André Hamelin began his recital Sunday afternoon at New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall with a soft, suggestive, fluid, enigmatic piece that he had composed himself. It was, as things turned out, a taste of things to come.

The rest of the program, consisting of a little-known sonata by Nicolai Medtner and a famous sonata by Schubert, unfolded in that same mysterious atmosphere of introspection, often teetering on the edge between intimate expression and ironic detachment.

Hamelin’s Barcarolle, composed last year, received its North American premiere Sunday. If listeners expected it to resemble Chopin’s erotically charged piece of the same title, they were in for a surprise. This Venetian boat song concerned itself with what was going on around the boat, not in it. Gentle left-hand arpeggios and rapid pianissimo swirls of notes in the right hand evoked broad waves and tiny eddies. Amid all this, a “three hands” effect produced songlike phrases in the middle register.

A passage in high, precisely voiced chords dwindled exquisitely from soft to very soft to barely perceptible. Elsewhere, the pianist-composer let the waters flow effortlessly around the keyboard, with a veiled sonority that owed less to Chopin than to the watery depths of Debussy’s Voiles or La cathédrale engloutie.

After that, it was a short step, at least in the pianist’s view, from Hamelin’s latter-day Impressionism to Medtner’s expansive (some would say overblown) twentieth-century Romanticism. Once again elemental forces were involved, since Medtner’s Sonata in E minor, Op. 25, No. 2, is subtitled “Night Wind” after the impassioned poem by Fyodor Tyutchev that serves as its epigraph.

The Russian composer, known for his thick piano textures and blizzards of notes, outdid himself in this lengthy single-movement work. “Oh, do not wake the sleeping storms,” pleaded Tyutchev in the poem. “Chaos writhes beneath them!” Seemingly ignoring the poet’s advice, Medtner unleashed a nearly unceasing whirlwind of chromatic modulations that threatened to sweep away his themes in a chaotic vortex.

On Sunday, Hamelin managed all this with elemental ease, etching the sonata’s themes clearly while the wind muttered, veered, and surged. His technique was so fluent and involved in the music that one could almost forget how many thousands of notes were pouring from the instrument.

The only thing missing from this performance was a sense of direction, of where one was in the composition. Maybe a piece representing Chaos shouldn’t have that anyway, but one wished for the occasional feeling of arrival somewhere—and not that of the closing pages, where Medtner repeatedly seemed about to end the piece with a big cadence, only to veer off into more musings, and ultimately to finish the work with a Rachmaninoffian shrug. Hamelin could have gauged the climaxes to make better sense of this section.

Likewise, in Schubert’s Sonata in B-flat major, D. 960, the pianist seemed more interested in mulling over each moment than seeing the piece in perspective. To the many pauses Schubert wrote into the score of the first movement, Hamelin added innumerable rubatos and hesitations, including some that became mannerisms, such as a little breath-pause before the top note of nearly every phrase.

Ultimately, however, Hamelin’s extraordinary control of touch and shading in the performance’s hushed dynamic proved mesmerizing, even if the piece sounded more like a dream about a sonata than a real one.

Similarly, the Andante sostenuto unfolded in a glacial quiet, more Adagio than Andante, but well “sustained” by the pianist’s intense concentration. A hearty interlude soon gave way to the first theme on another long diminuendo, superbly controlled and tinted in wintry shades. If one had issues with Hamelin’s introverted readings elsewhere in the program, they paid off handsomely here.

What to do, then, with the following scherzo, marked “lively, with delicacy”? Hamelin gave it a slightly frantic edge, a feeling of forced gaiety amid the dark meditations, and returned to soft, enigmatic utterances in the trio.

A similar air of je m’en fous hung around the rondo finale. In Hamelin’s light, mordant rendering, with dark shadows lurking in the diminuendos, even the exuberant Presto coda came off as ironic, a bit of noise for the groundlings.

Other performances of this sonata have shown us Schubert building anew on a Beethoven design. Hamelin on Sunday chose instead to meditate on the piece as an object, and ultimately to find Mahlerian resonances in it. It was three-quarters of an hour well spent.

For encores, the pianist circled back to Debussy with that composer’s Reflets dans l’eau, suitably liquid and exquisitely colored (and the more effective for being played strictly in time), then dazzled listeners with a curiosity, the Etude in A-flat major by Paul de Schlözer, an over-the-top efflorescence of scales and figurations for both hands.

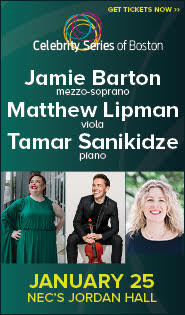

The next classical-music presentation of Celebrity Series of Boston is clarinetist David Shifrin, mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke, and the ensemble Opus 1, 8 p.m. Tuesday, January 28, 2014 at Pickman Hall, Longy School of Music. celebrityseries.org; 617-482-6661.

Posted in Performances