Nelsons, BSO open season in a freshened Symphony Hall with lively Mozart, swaggering Strauss

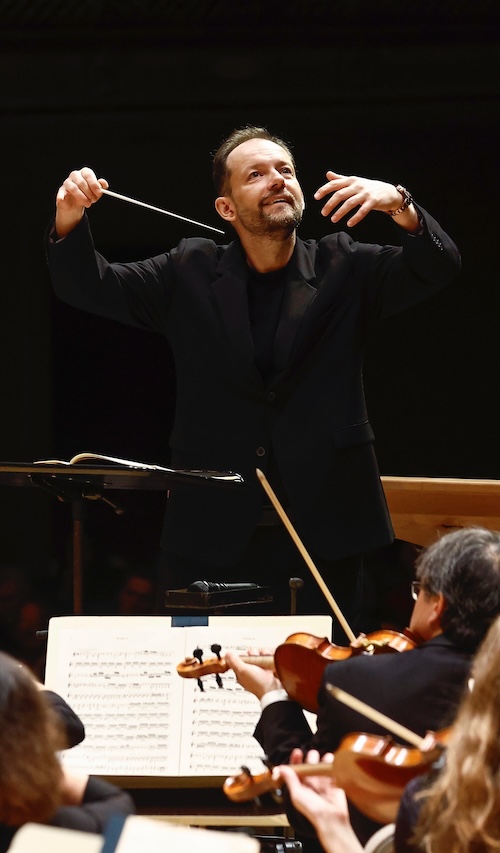

Andris Nelsons conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra in music of Mozart and Richard Strauss Thursday night at Symphony Hall. Photo: Winslow Townson

Nothing says “Happy 125th Birthday” like a gentle facelift.

Symphony Hall, which celebrates its quasquicentennial on October 15, received the former over the summer. The walls have been repainted, the carpeting has been refreshed, and the storied venue’s hallways and common areas now exude a bright, warm, welcomely nautical vibe.

The untouched hall itself looks a bit drab by comparison, but its matchless acoustic remains intact. And, while the short festival marking the big anniversary doesn’t officially kick off until next week, there was a celebratory aura surrounding Thursday night’s concert of music by Mozart and Richard Strauss from the Boston Symphony Orchestra and music director Andris Nelsons.

To be sure, the BSO has built a reputation as the country’s go-to ensemble for French repertoire. Yet its Germanic bona fides are considerable and, in summiting a couple of musical Alps—the “Jupiter” symphony (No. 41) and Ein Heldenleben—the orchestra demonstrated that it hardly needs to enlist a high-wattage soloist to generate musical sparks: it’s got plenty of flash and pop within its ranks.

Strauss, himself, has a direct link to both the BSO and Symphony Hall, having led the group in a concert from its stage in April 1904. And Nelsons, now in his twelfth season at the orchestra’s helm, is an old Strauss hand. Thus far, he’s led three of the composer’s operas and eight of the ten tone poems in town during his tenure.

Though his take on some of those works has bordered on turgid, Ein Heldenleben has been one of the maestro’s reliable calling cards, live and on disc. So, by and large, it proved again on this latest outing for the Münich-born master’s egocentric 1898 tone poem.

With a few exceptions—notably a spacious, slightly indulgent take on “The Hero’s Works of Peace” section—this was a Heldenleben that knew how to move. Rarely was the reading sidetracked by little things. Instead, it kept the score’s big picture firmly in view.

In Nelsons’ depiction of the hero and during the climactic battlefield movement, there was enough swagger and sweep from the BSO’s brasses—particularly the expanded horn section—to thrill the most fervent musical Teuton. The latter episode built to a pummeling din, but not an unbalanced one: the strings managed to speak through the rough-and-tumble and the combat between the massed winds and percussion was admirably well-matched.

Pleasing subtleties also abounded. Concertmaster Nathan Cole’s account of the extended violin solos that represent Strauss’s wife boasted artistry of tremendous range and style. Contributions from principal chairs across the ensemble showcased a collective that was clearly treating a late-Romantic warhorse like it was chamber music for 120 people. So did the finale’s faultlessly blended and balanced last chord, which was stunningly jewel-like: radiant, pristine, transcendent.

Those same adjectives belong to Mozart’s last symphony—the score, if not quite Thursday’s account of the same. Completed in 1788, this C-major essay is generally regarded as the greatest Classical-era symphony and one of the towering specimens of the wider genre (its Jupiter appellation is the work of a publisher, not the composer).

On this occasion, Nelsons and the BSO brought the same kind of energy and spirit to Mozart that they’ve lately been lavishing on Beethoven. Technically, the results were exhilarating: Thursday’s “Jupiter” was eminently fresh and lively, often leaning ever so slightly into the beat.

In the first movement and minuet, this meant that bold contrasts of dynamics and texture were the rule. Though the gorgeous Andante didn’t always achieve edge-of-the-seat pianos, it was beautifully shaped and the orchestra’s sensitivity to the subtle writing for woodwinds ended up drawing unexpected parallels between the 18th-century icon and his later admirer, Strauss.

Only in the finale did things go a bit sideways, interpretively, with Nelsons inexplicably omitting the repeat of its second half. A small thing, perhaps, but the context of that indication—in the midst of some of the most spectacular and involved counterpoint in the canon—speaks volumes and is crucial: the composer’s considered judgment here needs to take precedence over a conductor. Nevertheless, the BSO’s playing in this most ingenious and brilliant of movements consistently sparkled.

The program will be repeated 1:30 p.m. Friday and 8 p.m. Saturday. bso.org

Posted in Performances