Zander, Boston Phil bring fresh insights to Bartok, Brahms and Beethoven

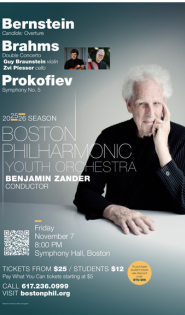

Guy Braunstein performed Brahms’ Violin Concerto with Benjamin Zander conducting the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra Sunday at Symphony Hall. Photo: Hilary Scott

“The aspect of things that are most important for us,” Ludwig Wittgenstein once wrote, “are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity.”

The great philosopher wasn’t speaking of orchestral programs, though, given their often-tight embrace of the repertoire’s fifty or so greatest hits, he might as well have been.

Yet close acquaintance with a body of music needn’t result in fustily dogmatic performances, as Sunday’s concert from the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Benjamin Zander reminded. To be sure, the afternoon’s offerings of works by Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, and Béla Bartók could hardly have been more canonic. Even so, there were moments of real revelation and charm, as well as stentorian pronouncement, to be had across it.

The latter quality surfaced most strikingly in Beethoven’s Egmont Overture. On Sunday, the weighty, measured attitude of the curtain raiser’s sober opening parts culminated in a purificatory “victory symphony.”

If tumult was the order of the day in Egmont, Brahms’s Violin Concerto preached serenity. That’s not necessarily what one expects in this expansive opus, with its huge expressive cast and the sometimes Bachian demands it makes on the soloist.

Yet in sharing the Symphony Hall stage with violinist Guy Braunstein, Zander had an ideal partner with whom to explore all of the score’s ebbs and flows. Back exactly one year after his debut with the BPO last year, the former Berlin Philharmonic concertmaster brought warmth and flexibility to his big first-movement solos, though his instrument—a violin made by Francesco Ruggieri in 1679—sometimes sounded a bit constrained.

Nevertheless, the Adagio sang with enchanting sweetness, Peggy Pearson’s oboe solos twining alluringly with Braunstein’s soaring lines. The finale, though a touch heavy-footed, brought the proceedings to a romping, zesty close.

Some moments of spotty intonation and aggressive tone aside, Braunstein’s charisma generally carried the day. He rewarded a lively ovation with a pair of encores: the “Sarabande” from Bach’s D-minor Partita and, before that, a fetching solo-violin arrangement of Fritz Kreisler’s Schön Rosmarin.

If the sheer elegance of much of the afternoon’s Brahms came as a welcome surprise, so did the flowing lyricism on display in Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. Written for the Boston Symphony in 1943, this music is no stranger either to the Philharmonic or Zander.

Sunday’s performance embraced the score’s explorations of sonority and character in equal measure. The first movement’s “tranquillo” episodes were just that: oases of otherworldly calm and beauty in the midst of turmoil. At the same time, its Allegro vivace sequences offered no shortage of limber energy.

In the second and fourth sections, Zander and the BPO ably captured the music’s espièglerie. While the cheekiness in “Game of Pairs” was offset by beguiling layers of glissandi, trills, and pattering sixteenth notes, the plangent viola theme of the “Intermezzo interrotto” offered a noble contrast to the movement’s snarky dig at Shostakovich.

Elsewhere, the eeriness of Bartók’s writing came across powerfully. The “Elegia” emerged as an impassioned, wailing song, the spinning woodwind figurations just before the end lending a touch of delirium to the proceedings.

And, in the finale, Zander didn’t give away the music’s game over the course of its many pages of exuberant counterpoint. Instead, he saved the performance’s best moments for the spooky buildup into the blazing coda. Here things very simple and familiar (mainly scales and canons heard earlier in the movement) suddenly revealed a landscape at once fresh and intriguing but also thoroughly unsettling.

Perhaps, in hindsight, this was the scene that the afternoon’s emotionally unsettled Egmont was portending. Perhaps not. Regardless, one could hardly have asked for a more satisfying interpretive reveal than what the crowning moments of this rightly popular fare delivered on Sunday.

The Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra performs works by Verdi, Dvorak, and Stravinsky 3 p.m. November 3rd at Symphony Hall. bostonphil.org

Posted in Performances