Argento’s magnificent score undone by muddled libretto, uneven singing in Odyssey Opera’s Poe voyage

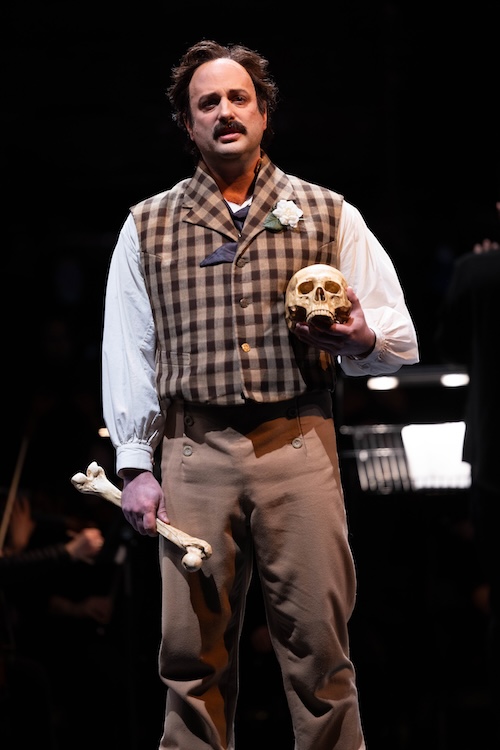

Peter Tantsits starred in Odyssey Opera’s presentation of Dominick Argento’s The Voyage of Edgar Allen Poe Friday night at the Huntington Theatre. Photo: Kathy Wittman/Ball Square Films

Considering the variety and invention of his writing, it’s surprising that Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories haven’t figured more prominently in the opera house. Then again, there’s no guarantee an adaptation of “The Masque of the Red Death” or “The Fall of the House of Usher” would have legs: the canon is a strange, capricious mistress, as composer Dominick Argento well knew.

The Pennsylvania-born, Minnesota-based composer wrote fourteen operas, yet only a couple have established themselves on the fringes of the repertoire. The Voyage of Edgar Allan Poe wasn’t one of them.

Commissioned by Lyric Opera of Chicago for the national bicentennial in 1976, the two-acter, which sets a libretto by Charles M. Nolte, imagines the great writer revisiting the highlights of his life in a series of hallucinogenic flashbacks the night before his death.

The concept itself makes for a packed three hours. In Odyssey Opera’s production of Voyage that Gil Rose conducted at The Huntington Theatre on Friday night, you felt each one of them.

Primarily, this was because Nolte’s contribution came across as muddled.

At its best, his effort emphasizes the connections between Poe’s art and his lived experience: references to “The Bells,” “Annabelle Lee,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “Ulalume,” “The Raven,” and “Eldorado” (among others) are deftly tied into the narrative. What’s more, Nolte’s characters are fully formed and his attempts to redeem Poe’s legacy from the calumnies of frenemy Rufus Wilmer Griswold are noble and, largely, successful.

More problematic are the ways in which they the action is framed. Voyage is cast in a dour pair of acts split into ten scenes plus a prologue and epilogue. Most of the tale unfolds in Poe’s mind, taking place during an imagined ship journey to Baltimore. In good, horror-movie fashion, several characters transform into doubles as the opera proceeds.

There’s a Freudian element, too, as the harassed Poe is tormented by visions of his deceased mother: in one scene, she’s cavorting with Griswold; in another, her shadow offers herself, seductively, as the author’s muse. Additionally, in Act 2, he’s put on trial for supposedly wishing for (or is it enabling?) the premature death of his wife, Virginia, so that his macabre creativity might thrive.

Taken together, this makes for a pretty bleak and confusing evening, even without the tacked-on courtroom scenario.

Whatever redemption is to be found, then, is had in the music. And Argento’s score is a marvel of color, drama, and fantasy. Not once across Voyage’s long runtime is there the sense of the composer spinning his wheels or struggling to match the dramatic demands of the moment.

Instead, in many ways, the score showcases, like Poe, an artist at the height of his creative powers. There’s harmonic pungency and dissonance galore, but never just for its own sake. More striking are Voyage’s discreet motivic connections, like the opening’s pulsing timpani beats that transform into dirge-like figures depicting the sea and, later, morph into a stately, treading wedding march.

Though the opera is split into a dozen sections, Argento connects them seamlessly. Perhaps his most impressive compositional achievement is the music’s sheer fluency: everything seems to flow with natural, imperceptible logic.

Together, all this might result in something transforming. Instead, Friday’s performance was limited by the confines of the venue: since the big orchestra wouldn’t fit in the pit at the Huntington, they were onstage behind the singers and wreaked the usual havoc with balances.

Still, there’s no question that Odyssey’s cast brought intensity to bear in Voyage.

Peter Tantsits’ Poe sang with palpable fervency. Unfortunately, his diction, especially in Act 1, was only fitfully intelligible.

The same went for much of the rest of the cast, especially in ensemble numbers. Between the lack of subtitles and diction, much of the evening passed as a veritable Babel, the full librettos Odyssey distributed rendered moot by the blacked-out hall.

Tom Meglioranza’s villainous Griswold proved an exception, managing to project with clean, consistent brilliance (such brilliance, in fact, that he earned a few boos during his bows).

Maggie Finnegan’s pure-toned Virginia was likewise agreeable, soaring in her haunting Act 2 scenes. So too was David Salsbery Fry as the Theater Director, and the war of the Odyssey Opera Chorus, which sang throughout with snapping clarity and good blend.

Though sometimes too prominent, the stars of the evening were the members of the Odyssey Opera Orchestra, who dispatched Argento’s kaleidoscopic writing with freshness and assurance. Rose was firmly at home in the composer’s style, and presided over a reading that was rhythmically secure and smartly shaded.

It was also sonically compelling. Voyage’s big moments – the sumptuous climax of Scene 2, the bracing end of Act 1, the trumpet fanfares leading into Scene 8, among them – rightly thrilled. But it was the delicate spots, like the viola/cello duet in Scene 6 and Virginia’s aria with chimes in Scene 7, that held the ear (and house) rapt.

Though confined to the front third of the Huntingon’s stage, the production itself was a model of limited precision. Anne Harley’s direction ably utilized the space, while Brooke Stanton’s costumes and Rachel Padula’s hair and makeup design firmly established the action circa 1849.

Posted in Performances