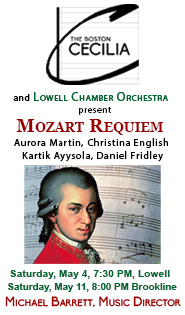

Under Canellakis, worlds collide and cohere with BSO’s Bartók and Haydn

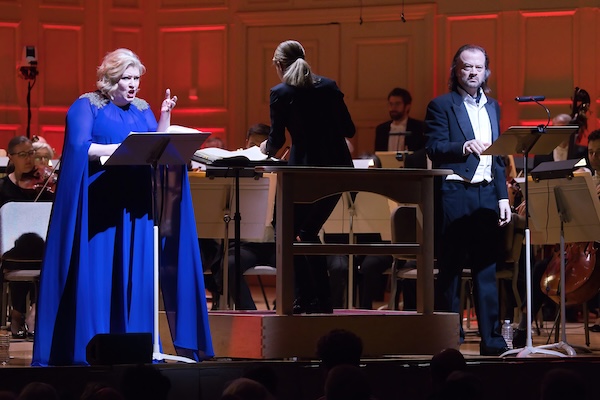

Karen Cargill and Nathan Berg were soloists in Bluebeard’s Castle Thursday night with Karina Canellakis conducting the BSO. Photo: Hilary Scott

On the face of it, Franz Josef Haydn and Béla Bartók don’t have much in common. The latter was one of the 20th century’s most uncompromising Modernists. Haydn, on the other hand, was a model of Enlightenment wit, resourcefulness, and eloquence.

But look or listen closely and striking similarities start to emerge. Both composers left a personal stamp on every genre in which they composed. Both were masters of invention. Both spent the bulk of their careers in Hungary and freely drew on that region’s folk tunes and sources.

Though Thursday night’s concert from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which paired Haydn’s C-major Cello Concerto and Bartók’s opera Bluebeard’s Castle, superficially played up their big contrasts—particularly the sunny ebullience of the former versus the psychological turbulence of the latter—several parallels were still to be found.

That was largely due to conductor Karina Canellakis’ thoughtful, essentially lyrical approach to both works. The 42-year-old chief conductor of the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra has been a regular BSO guest since 2021 and Thursday’s appearance built considerably on her impressive Symphony Hall debut last January.

At the heart of the evening was Bartók’s 1911 setting of a libretto by Béla Balázs. Adapted from a folktale first published in 1697, Bluebeard’s Castle tells the story of a newly married couple, the titular Duke and his bride, Judith. On arriving for the first time at her husband’s abode, the latter demands that he let her open seven locked doors. Despite Bluebeard’s protestations, she proceeds, at the very end discovering his three previous wives, who have been locked away for eternity. As the curtain falls, Judith joins them.

Thursday’s Judith, Karen Cargill, led the way with some gleaming high notes and a steely lower register. Though her mid-range contributions were periodically muddled and Cargill’s softest utterances didn’t always project above the orchestra, the mezzo brought fire to her character’s demand for the final door to be opened.

Filling in for the indisposed Johannes Martin Kränzle, Nathan Berg’s Bluebeard was marked by dark-hued resonance and stentorian nobility. Though this character rarely comes over sympathetically, the bass-baritone did manage to breathe some warmth into a figure who occasionally looms as little more than an automaton villain.

Jeremiah Kissel intoned the short opening narration with winning theatricality. For the spoken part, he utilized Peter Bartók’s English translation of the libretto; the remainder of the performance was sung in Hungarian.

Canellakis presided over everything with surety. Leading the BSO in their second operatic performance in two weeks, she drew out Bluebeard’s frightful gestures and grating dissonances with biting urgency. Yet even the eeriest of them (like the shimmery swirling motive depicting the Lake of Tears and the unsettling transition into the Armory Scene) were couched in a songful warmth one doesn’t often encounter in this music.

Her reading was fully alive to Bluebeard’s myriad details. Tempos moved smartly. Textures were consistently limpid. The ensemble carefully observed the score’s enormous dynamic range. Accordingly, its delicate instrumental details spoke clearly. Though the inevitable balance issues between singers and huge orchestra sometimes cropped up, most of what needed to be heard came out readily.

The BSO’s tonal blend, both sectionally and across the expanded ensemble, was often sublime. So gripping was the explosive instrumental depiction of Bluebeard’s kingdom— and so flawlessly balanced—that one hardly minded that Cargill’s climactic high C had been completely swallowed up by the orchestra. The anguished climaxes before the closing of the seventh door proved likewise affecting.

Prefacing Bluebeard, Haydn’s 1765 effort offered comparative harmonic and expressive simplicity. Even so, the score’s allusions to the Baroque concerto form (as well as its anticipations of the Classical iteration), unpredictable turns of phrase, and head-spinning virtuosity kept Thursday’s performance from ever feeling too settled or predictable.

So did the playing of the night’s soloist, Alisa Weilerstein.

Alisa Weilerstein performed Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major with Karina Canellakis and the BSO. Photo: Hilary Scott

A cellist with an exceptional command of the notes and grasp of the spirit of the music, she executed her part with considerable panache and character. While Weilerstein’s phrasings in the first movement felt somewhat stiff and boxed-in, the cellist found her footing in the Adagio and brought plenty of mischievous energy to the finale. Her encore of the Sarabande from Bach’s E-flat Major Cello Suite was a picture of concentrated serenity.

As in the Bartók, Canellakis led an accompaniment that was focused on the details, but never at the expense of the bigger musical picture. The outer movements were crisp and spry, the middle one rhythmically taut and beautifully shaped.

While the orchestra’s reduced contingent was a concession to period practice, its polished sonority resulted in a sheen that was uncomfortably bright. Still, the players’ diligent attention to full-bodied dynamic contrasts ensured that Thursday’s concert offered the most satisfying Haydn heard from the BSO in a long time.

The program will be repeated at 1:30 p.m. Friday and at 8 p.m. Saturday at Symphony Hall. bso.org

Posted in Performances