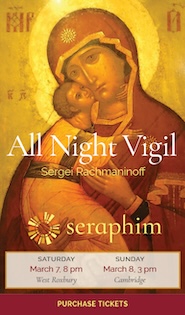

Seraphim Singers mark 25 years with a celebration and homage

Jennifer Lester led the Seraphim Singers in a program titled “Seraphim and Other Angels” Saturday night in Brookline. Photo: Nick Welles

Some season finales feel bigger than others. Take The Seraphim Singers’ concert Saturday night at Brookline’s All Saints Parish. On the one hand, their program, led by music director Jennifer Lester, was celebratory, marking the ensemble’s silver jubilee. Simultaneously, though, the night memorialized John Dunn, a former Seraphim board member, mentor, and patron who passed away last year.

In practice, the evening, which included a mid-concert sing-through of Dunn’s paraphrase of Psalm 136 (among other things, he was an avid church musician), fulfilled both functions admirably. It also offered a couple of musical curiosities, the most striking of which was Benjamin Britten’s cantata The Company of Heaven.

Written for a BBC radio broadcast in 1937, Britten’s score is singular. For one, it draws heavily on the spoken word: a narrator (or, on Saturday, a pair of them) recite texts about angels drawn from a variety of sources, ranging from the Bible to John Bunyan, William Blake, and Francis Thompson, as well as early-20th-century poets. These are interspersed with a series of solos, duets, choruses, and instrumental movements.

The contrast between the two—the stuffy, quasi-Victorian voice-over and Britten’s freshly fluent, if not yet sheerly original, music – is stark. While the latter often soars, the former frequently sags.

That it did so Saturday, despite the firm, articulate contributions of speakers Richard Tarrant and Rhea Yvonne Ranno, perhaps says it all. Indeed, one couldn’t help but wonder if, absent its long-winded, documentary-like commentary, The Company of Heaven might make a repertoire staple.

The score is full of fascinating, forward-looking strokes, and certainly makes a case for itself. Hints of what’s to come are evident practically from the downbeat: the instrumental “Introduction” uncannily anticipates the disorienting opening measures of Britten’s 1962 War Requiem.

Meanwhile, “Christ, the fair glory” evokes the spirituals of Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time and the violent sprechstimme interjections in “War in heaven” wouldn’t be out of place in William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Throughout, Britten’s harmonic language, though broadly diatonic, doesn’t shy away from evocative dissonances— nor sensuous warmth.

On Saturday, the last crept in, ethereally, in “Heaven is here,” a beguiling movement whose gentle, undulating textures and harmonic progressions are reminiscent of Les illuminations. Likewise affecting was the Singers’ delivery of the queasy chromatic turns in “Whoso dwelleth under the defense of the most high” and their radiant account of the closing bars of “Ye watchers and ye holy ones.”

Though balances in more aggressive movements were uneven— “The morning stars” sounded underpowered and one wouldn’t have minded twice as many voices conjuring the “War in heaven”—Saturday’s reading still managed to capture much of the character of this music.

That was certainly true of the excellent soloists: soprano Barbara Allen Hill and tenor Thomas Valenti both sang with color, stamina, and control. Hill sounded luminous in “Hail Mary” and “Heaven is here.”

Meanwhile, Valenti delivered “A thousand thousand gleaming fires” with a lightness and precision worthy of Peter Pears. The pair also blended well during their handful of ensemble numbers, especially the central duet in “Ye watchers and ye holy ones.”

Lester directed with a sure grasp of the music’s structure and style. Though the ad hoc instrumental ensemble’s contributions weren’t always as tonally or rhythmically secure as one might have wished, they generally conveyed the score’s shifts of color, especially in the “Funeral march for a boy” and during the strings’ invigorating imitations of trumpets just before the finale.

The remainder of the evening featured the Singers in a mix of accompanied and a cappella fare. In the latter selections, the group often impressed for blend, tonal warmth, and attention to dynamic shape. They imbued Josef Rheinberger’s Abendlied and the energetic closing section of Piotr Tchaikovsky’s The Cherubic Hymn, especially, with healthy doses of all three.

Michael Burgo’s Song of the Seraphim proved less memorable: the music is flaccidly shaped, though Saturday boasted a clean, ringing soloist in tenor Jason Connell. While James Woodman’s insistently strophic adaptation of Psalm 96 cried out for bigger climaxes, the choir’s singing was rhythmically solid, as was their enunciation of the active lyrics.

Interestingly, Charles Villiers Stanford’s Te Deum laudamus is also bedeviled by the problem of a too-busy text. But the Dublin-born composer found a surefire way around it: blunt force. Moments in this 1897 score are unwieldy and awkwardly wordy, yet the jubilant flow of the music carries all before it.

Which is exactly what happened Saturday with Lester and the Singers robustly navigating their parts and organist Heinrich Christensen providing a snapping, carefully balanced accompaniment. The cumulative effect was, if not the night’s most rousing moment (those came in the Britten), then its most unabashedly festive.

Posted in Performances