Zander leads Boston Philharmonic in boldly projected Bruckner

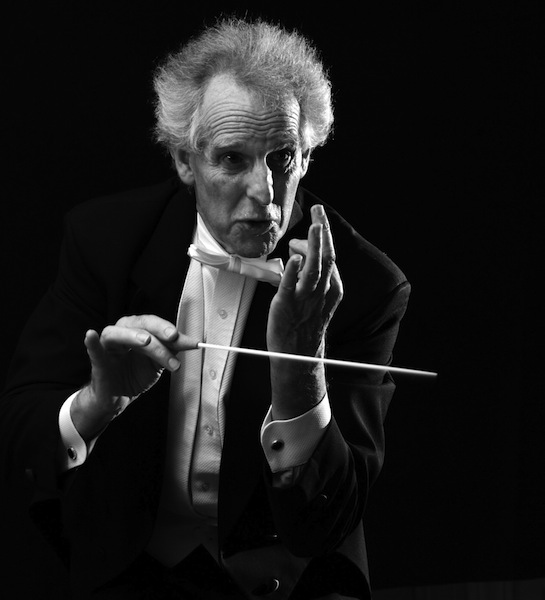

Benjamin Zander conducted the Boston Philharmonic in music of Bruckner and Beethoven Saturday night.

Large-scale orchestral works seem tailor-made for Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic. In the past few seasons, the orchestra has explored symphonies by Mahler, Rachmaninoff, and Tchaikovsky, as well as Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. The music of Bruckner has remained close to Zander’s heart, and Saturday night at Jordan Hall, the conductor led the Boston Philharmonic in a bold and exciting performance of the composer’s Ninth Symphony.

Bruckner found little sympathy in his day from music critic Eduard Hanslick, who panned the composer’s symphonies for being too reminiscent of Wagner. There’s certainly a touch of the sage of Bayreuth’s style in Bruckner’s scores. Brasses build to gleaming climaxes. Strings churn away on waving chords. In essence, Bruckner’s music, like Wagner’s, is elemental, with sounds seeming to emanate from deep in the earth.

That’s certainly true of the Ninth Symphony. Left incomplete at the time of Bruckner’s death, the symphony, in its three movements, conveys a sense of the otherworldly.

Architecturally, the piece is like a cathedral in sound, with sections unfolding in long episodes that have their own sense of tension and release. Some are earthy and evolve from chords that reach from growling depths to powerful heights. Other sections are warmly lyrical.

Saturday night, Zander was finely attuned to most aspects of this searching work, and drew playing of cutting power. This was Bruckner cast in bright, primary colors.

There are certainly places in this symphony where that approach paid dividends. Climaxes were sturdy, and even soft passages, which seemed to come from nowhere, glowed with intensity. The brasses supply the grandeur to this symphony, and the Boston Philharmonic musicians were up to the challenge as the French horns sounded out the opening theme with precision and commitment. The most effective playing came in the Scherzo, which, in Zander’s interpretation, is Bruckner’s terrifying vision of hell. The orchestra dug in for the angular statements that form the height of the movement.

Missing from this performance, though, was a sense of enveloping, reverential warmth in the closing Adagio. The strings, which supply the humanity of this piece, sounded with more radiant intensity than distant glow. Zander, though, found the finer details of the score, coaxing fine playing from solo flute and oboe in the final movement.

The performance also suffered from a few moments of imprecision. Pizzicatos in the second movement were not together, and there were some tentative attacks and cracked notes from the Wagner tuba in the third movement. The loud sections brought out the best playing, and Bruckner’s thorny dissonances blazed appropriately in these passages.

The orchestra dedicated its performance of the Ninth Symphony to the memory of Don Davis, who played principal trombone for the ensemble for 38 years. The symphony’s closing phrases seemed to rise heavenward in a fitting tribute to his life.

The first half of the concert was dedicated to Beethoven’s Triple Concerto, which starred members of the Boston Trio as soloists.

Though it has been the source of derision from critics ever since its inception, the Triple Concerto is a tasteful work shot through with fine tunes. Its solo passages demand players who possess firm technique and singing tone.

The Boston Trio delivered all that and more Saturday night. The musicians, violinist Irina Muresanu, cellist Jonah Ellsworth, and pianist Heng-Jin Park, play together with an elegant, chamber-like cohesion. The players delivered the edge so essential to Beethoven’s music, yet they could come away from that intensity when called upon to perform phrases of silvery lyricism. Theirs was a colorful rendition of the score.

In the first movement, the trio traded running figures between each other with dexterity. The singing passages were beautiful. Ellsworth’s cello tone, at times dry, at others radiant, blended smoothly with Muresanu’s bright-toned violin. Park’s supporting arpeggios and scales were crisp and nimble. The second movement moved fluidly, with the trio engaged in sun-lit phrases. Zander wove a soft bed of accompaniment through gentle rubato.

The finale is a polonaise where dance-like passages brush up against brilliant flourishes. The trio handled it all with the verve of a village band. Some of the tricky phrases brought a few pitchy notes in Muresanu’s violin. A quick retuning fixed those problems, and trio dug in to finish the piece with abandon.

Zander led an accompaniment of romping energy, which brought a rousing conclusion to the work.

The program will be repeated 3 p.m. Sunday at Sanders Theatre. bostonphil.org

Posted in Performances