Emmanuel Music’s skillful “St. Mark Passion” fails to make a Bach case

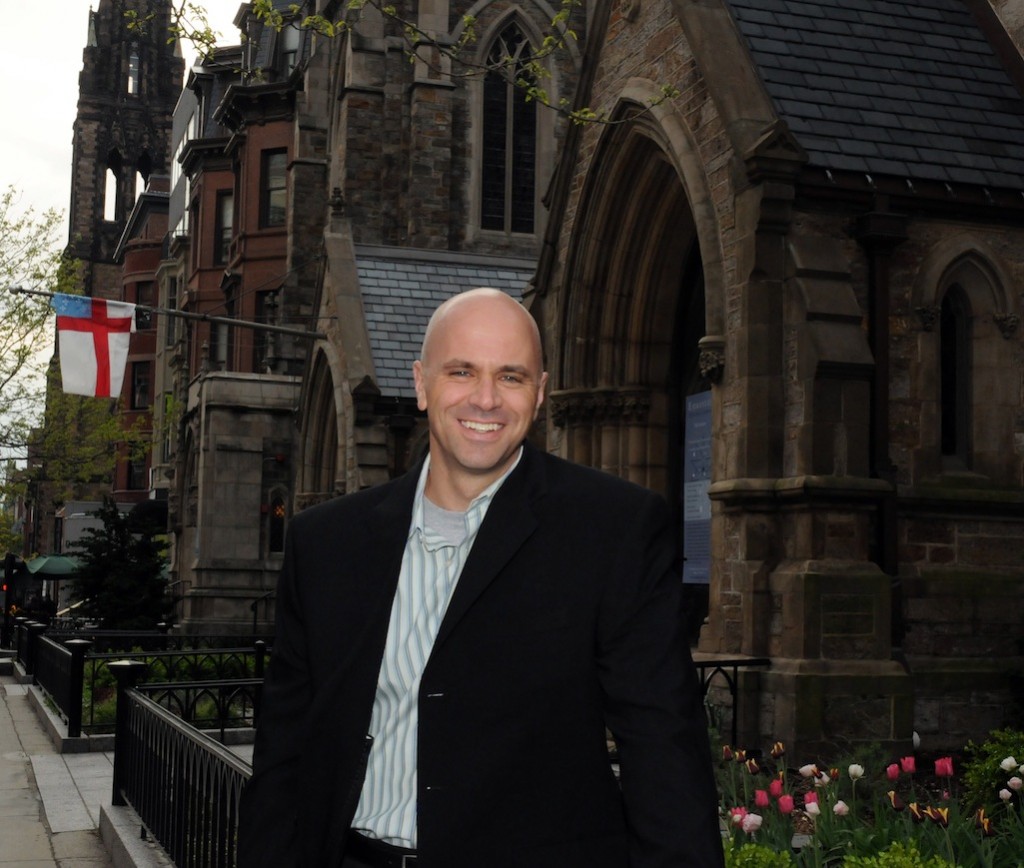

Ryan Turner led Emmanuel Music in a conjectural rendering of Bach’s “St. Mark Passion” Saturday night.

Emmanuel Music’s concert of music by J.S. Bach and others, billed as a “reconstruction” of a lost Bach work, The Passion According to St. Mark, left a lot of questions unanswered, the most salient one being: Why?

Saturday’s skillful performance at Emmanuel Church tried to justify itself by means of often-mystifying program notes, but not even these claimed that what was being performed Saturday was an actual work by Bach—or even a plausible version of what was heard at that Good Friday service in Leipzig in 1731 for which Bach provided the music.

The essay acknowledged that not a note of what was performed on that occasion is now known, nor is there any indication which of his previous works Bach might have borrowed from to assemble a St. Mark Passion. (This method, known as “parody,” has a long and honorable history in music, and Bach used it often.)

What does survive is the written text of a St. Mark Passion in the collected works of the poet who called himself Picander, whose words Bach often set to music. This is thought—on what grounds, the program didn’t say—to have been the text Bach set in 1731.

Next we have Wilhelm Rust, the editor of Bach’s complete works and cantor of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, who in 1873 “realized” that Bach had used “five movements” from his Trauer Ode, BWV 198 in the St. Mark Passion. The program didn’t explain how Rust knew that, but it did say that “this music provides us with three choruses and three arias.” (That’s six movements, but never mind.)

Leaning on this frail reed, musicologists and performers have produced, by Wikipedia’s count, at least eight different “reconstructions” of the St. Mark Passion (one of which doesn’t even use the Trauer Ode). Their common goal was to produce a plausible “work by Bach” using the parody technique. There was, in fact, no “re” involved—these were Bach “constructions,” plain and simple.

Bach, however, was as great a master of parody as of everything else. He was like that friend of yours who can look in your refrigerator, find just a hot dog, a can of beer, and a bag of chocolate-chip cookies, and whip you up a gourmet dinner. Bach could make a bunch of pieces composed 20 years apart sound like a single flash of inspiration.

Apparently, in quest of a similar effect, Emmanuel Music artistic director Ryan Turner and musicologist Christoph Wolff (guided in part by previous constructors’ efforts) went shopping in Bach’s vast oeuvre for arias and choruses that fit Picander’s text and that set the right mood for that point in the story. They did pretty well at that, but not to the point of creating a unified, compelling narrative like Bach’s two surviving Passions.

It would seem that, no matter one’s level of expertise—and it’s safe to say these two know their Bach as well as anybody on the planet—to create a Bach “work” from so little evidence is about as plausible as a panel of Beethoven scholars getting together to compose a Tenth Symphony.

The most coherent aspect of Saturday’s performance was the Gospel narrative itself, which was not by Bach but borrowed from a St. Mark Passion by his contemporary Reinhard Keiser, a work Bach is known to have performed. (Recitatives by latter-day constructor Simon Heighes filled in a part of the Picander text not set by Keiser.) If these recitative passages lacked the harmonic daring and voice-stripping intensity of Bach’s Evangelist roles, they were at least conceived together as part of one work, and sounded so.

Any dramatic deficiencies in Keiser’s settings were more than made up for by the vivid storytelling style of Jason McStoots as the Evangelist, who dropped his pleasing tenor almost to a whisper for intimate scenes such as Peter warming himself by the fire, then swelled to a roar when describing Christ confronting his accusers before an unruly crowd.

Interpreters of the role of Jesus have to choose whether to emphasize the familiar human aspect or the unknowable divine. Baritone Mark McSweeney tended toward the latter, his bold utterances somewhat clouded by a wide vibrato.

It was a defensible choice, maybe even true to church practice in Bach’s time, but, especially in St. Mark’s down-to-earth Gospel, one might wish for the human touch at moments such as Jesus’s exasperation with his disciples for dozing off at Gethsemane (“Could you not stay awake for one hour?”).

The role of Pilate, briefer and less fleshed out in Mark than in the other gospels, was delivered with vocal focus and appropriate authority by tenor Charles Blandy.

The text’s abundance of chorales was supplied with actual Bach chorale settings, though with no possibility of rewriting the harmonies to fit the story, as Bach did so memorably in his St. Matthew Passion. The first few chorales were sung rather objectively, congregation-style, but later conductor Turner introduced inflections of tempo or dynamics in response to a striking harmony or image in the text.

For the most part, the singing of the 18-member chorus was a model of ensemble, German diction, and contrapuntal clarity. No fewer than eight singers stepped out of the ranks to sing the arias, mostly quite effectively. Altos Margaret Lias and Deborah Rentz-Moore and bass David Tinervia were among the standouts for carrying power and interpretive nuance.

The same observation applies to the small, tight instrumental ensemble, modulating their modern instruments to match more closely the ancient lute and two violas da gamba among them, and phrasing superbly together under Turner’s gently wielded baton. Players such as oboist Peggy Pearson, violinist Heidi Braun-Hill, and cellist Rafael Popper-Keizer rose from their chairs (well, maybe not Popper-Keizer) to provide vivid obbligatos to the arias.

The continuo group consisting of Popper-Keizer, lutenist Olav Chris Henriksen, gamba players Laura Jeppesen and Emily Walhout, and organist Michael Beattie provided lively support to recitatives and some of the arias.

Maybe this was the answer to “Why?”—highly polished, often affecting performances of a potpourri of music by Bach and Keiser, draped over a Passion text. But please don’t call it a “reconstructed” work by Bach.

This performance concluded Emmanuel Music’s evening concert series for 2015-16. The Bach cantata series at Emmanuel Church continues 10 a.m. every Sunday through May 15. emmanuelmusic.org;617-536-3356.

Posted in Performances