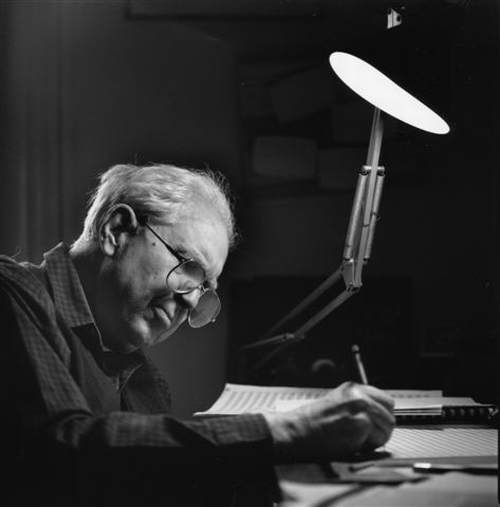

Collage New Music’s Carter program illuminates a challenging oeuvre

On Sunday night, the chamber group Collage New Music discovered the cure for Elliott Carter-phobia: Carter, Carter, and more Carter.

No fewer than ten works by one of America’s most praised, least understood composers graced the group’s program in Longy School of Music’s Pickman Hall. That devoted the group’s entire final season concert to plead the case of a man whose music, when flanked on a program by the likes of Schubert and Dvořák, can sound like the monster in the attic (Don’t go up there, Krissy!).

It was quite a different scene from those evenings at the Boston Symphony Orchestra when then-music director James Levine used to give his large audiences their dose of Carter whether they liked it or not. (Many did like it, but many others didn’t.)

On Friday, an audience of about 50 hardy souls—apparent median age about 70, mere kids compared to the late centenarian composer– was scattered around the tiny hall as Collage members Catherine French, violin; Joel Moerschel, cello; Christopher Krueger, flute; Peggy Pearson, oboe; Robert Annis, clarinet; and Christopher Oldfather, piano and harpsichord, joined by soprano Tony Arnold, bravely climbed the stairs and swung open the attic door.

What they found there was no scary creature, but an energetic, genial fellow of uncertain age—the composition dates ranged from 1939 to 2011—with a seemingly inexhaustible imagination, a flair for making instruments sound good individually and together, and a surprisingly traditional turn of phrase amid the atonal goings-on.

And if one had the impression that to understand a Carter piece required dividing the measure into 48 sub-beats and multiplying by 13, and then doing it all again backward, these performances showed that, thankfully, there were other routes into this music.

But where to begin? While Beethoven had to make do with three creative periods, the long-lived Carter (1908-2012), according to a comment by composer John Heiss in the program, had five: Tonal, Neo-Classical, Chromatic, Late, and Late-Late.

While touching on aspects of the first three styles, Friday’s program kept coming back to the late and later works, with their lyricism and celebration of longtime musical friendships. Presumably Carter would have approved— reportedly he, like most composers, preferred talking about his new pieces rather than his old ones.

Carter was already an old-timer of 34 when he penned the song Voyages No. 3 in 1943, to a poem by Hart Crane, in which imagery of ocean and sky blossoms into an erotic phrase (“Your body rocking!”) at the song’s climax. Friday’s bold performance by singer Arnold and pianist Oldfather eschewed Debussyan mist and sea-foam in favor of percussive piano tone and vocal sound with an expressive touch of roughness.

Although Carter had already composed his knotty String Quartet No. 1 when he began his Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello and Harpsichord in 1952, he showed mercy to the commissioning harpsichordist Sylvia Marlowe by writing in clear, open textures, even recalling his earlier style with a folksy touch here and there.

In fact, during the first movement and much of the second, the harpsichord had little to do but play slow, single-note lines for the other players to bounce off of. But then Oldfather got to show his mettle with a bit of jazz in the second movement and a cockeyed gigue and perpetual motion in the third.

The other three instruments, especially the flute and oboe, imitated the harpsichord’s pinging tone in places and took wing in others, alternately bumping into each other contrapuntally and vibrating brilliantly together.

All the evening’s players took the stage next—a seventh Collage member, percussionist Craig McNutt, was absent, and with him Carter’s vivid works for that medium—to watch each other dip into a box of musical valentines, brief solo works Carter had composed for friends and supporters.

Violinist French gave an eloquent, spirited rendering of Rhapsodic Musings (2000) an 80th-birthday gift to Robert Mann that displayed the violin in all its singing, slashing, leaping glory. In Steep Steps for bass clarinet, composed in 2001 for Virgil Blackwell, clarinetist Annis glowed, honked, whispered, bounded and danced, savoring the instrument’s pure top tones and trenchant deep staccato.

Oboist Heinz Holliger was the honoree of Figment VI, one of several pieces composed by the prolific centenarian in 2011; oboist Pearson was assertive in the high range and singing in the middle before tapering to a soft vibrato. Pianist Oldfather and cellist Moerschel then rewound the tape 72 years for Carter’s 1939 piece Elegy, a frankly tonal composition whose tender serenity and lush harmonies of the ninth were reminiscent of Poulenc.

Moerschel followed with Figment II—Remembering Mr. Ives, a solo cello piece rich in euphonious double stops and Ivesian allusions, composed in spring 2001 for Fred Sherry. Flutist Krueger closed this fine set of solos with Scrivo in Vento (I Write in Wind), Carter’s 1991 tribute to flutist Robert Aitken, vividly sculpting the piece’s soft lines and piercing shrieks inspired by the paradoxes in a poem by Petrarch.

Leading off the program’s second half, Christopher Oldfather bought virtuoso technique to the brawniest music of the evening, the two-movement Piano Sonata of 1945-46. In Oldfather’s hands, Carter’s score sounded richly idiomatic for the instrument, beginning with full, Brahmsian sonorities in big octaves and chords, and going on to blindingly fast, syncopated passages and a broad, legato chorale.

More breadth, and wide “American” intervals, also characterized the second movement’s Andante sections, which framed a vigorous fugue with a twisty subject. Oldfather fully realized the fugue’s Prokofiev-like energy and brilliance, with hints of boogie-woogie here and there, and if he wasn’t quite able to keep the Andante windup from seeming too long, his broad-shouldered performance overall earned vigorous applause.

There were no longueurs in the song cycle Tempo e tempi (Time and Times) of 1998-99, for soprano, violin, cello, oboe (doubling on English horn) and clarinet (doubling on bass clarinet), a collection of eight poetic vignettes, some only a line or two long. Collage music director David Hoose conducted the ensemble, ably managing this composer’s characteristic metrical complexities.

Bypassing the disjunct vocal lines favored by some of his contemporaries, Carter floated the soprano phrases smoothly, sometimes even conversationally, over picturesque instrumental parts. In the title song, a poem by Eugenio Montale speaking of paths “that rarely intersect” inspired terse instrumental phrases in Carterian multiple meters under a passionate vocal line.

In contrast, the tiny song “Una Colomba” (A Dove) intertwined soft singing with cooing sounds in the flute. Whether soaring, murmuring, or declaiming, soprano Arnold found the right character for each song, and her colleagues supplied commentary both supportive and ironic, and some vivid musical imagery as well.

By all accounts, Elliott Carter the man was good company. Two hours in the company of his music, so eloquently realized by the artists of Collage New Music, also proved to be time well spent.

Posted in Performances