Collage New Music remembers Gunther Schuller with a posthumous world premiere

On Sunday night, the chamber ensemble Collage New Music added its uncompromisingly modern voice to the chorus of tributes to the late composer and educator Gunther Schuller.

True to its name, the group presented two world premieres and a Boston premiere in the intimate Pickman Hall at the Longy School of Music of Bard College.

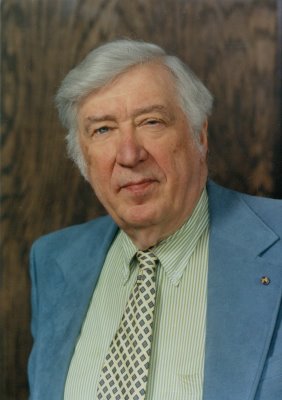

One of the premieres had a bittersweet (but mostly sweet) air about it, as the evocative vocal work Singing Poems had been composed for Collage New Music by Schuller himself shortly before his death last June. The new piece proved so vital and alert to its texts that, for a moment at the end, one fully expected to see the composer join the musicians onstage for the bows, displaying his familiar craggy profile and ready smile.

It still came as a shock to think that this sight, so familiar to Boston audiences over the years, would never be seen again.

But for most of the evening, somber thoughts were banished by delight in the inventiveness of the music and the players’ individual and ensemble virtuosity. Conductor David Hoose was a reliable timekeeper in complex rhythms, energizing the performance while finding the balances and tonal blends that made each piece sound its best, from the most raucous outbursts to the most attenuated textures.

In fact, Longy School faculty member Paul Brust’s Towards Equilibrium began with both of those things, a fiery cacophony followed by a frozen landscape of barely audible single notes. The reconciliation of these opposites was the business of this composition, which was receiving its world premiere.

That the piece was so overtly “music about music” only added to its fascination as the two elements circled each other, with the anarchic music gradually finding a sense of order and the isolated notes coalescing and moving to a pulse.

It eventually became clear that all these widely diverse episodes were variations on just two series of chords, which finally emerged in the work’s serene closing pages, bringing the piece to a satisfying conclusion.

The piece was also distinguished by Brust’s economical and imaginative handling of Collage New Music’s distinctive instrumentation and its skillful players: Catherine French, violin; Joel Moerschel, cello; Christopher Krueger, flutes; Robert Annis, clarinets; Christopher Oldfather, piano; and Craig McNutt, percussion.

In a leap from the abstract to the picturesque, Boston got its first chance to hear Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon’s Páramo, a vivid response to the Mexican novel Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo. Mexican-born himself, the Eastman School-based composer evoked the novel’s disruption of time with ticks, tocks, chimes and even a cuckoo, all gone wonderfully awry.

Opening with avian chirps and squawks, the piece developed a touch of stamping Mexican rhythm and a lean, Histoire du soldat-style sonority before expiring drolly amid the spasms of a clock running down. Percussionist McNutt, obviously the man of the hour in this piece, kept his timekeeping noises subtle and witty.

For the premiere of Singing Poems, the ensemble’s co-founder Frank Epstein joined McNutt in managing what Hoose called “Gunther’s late indulgence,” a stage-crowding battery of percussion.

According to a note in the program by Schuller’s longtime assistant, the commission for Singing Poems gave the composer an excuse to read a wide variety of poetry, something he loved to do but rarely had time for. His selection of texts ranged from John of the Cross to Shakespeare to Emily Dickinson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Gertrude Stein, and e.e. cummings.

The players and soprano Mary Mackenzie made clear what caught Schuller’s fancy about each text. An arresting presence onstage, Mackenzie intoned the poems in a clear, agile voice, capable of rising to a piercing cry that rivaled Krueger’s shrieking piccolo.

In these musicians’ hands, the spiritual ecstasy of John of the Cross’s “Deep Rapture” surged to almost violent passion, while Shakespeare’s “O Mistress mine” was sung insinuatingly as the instruments all but leered. Dickinson’s “Musicians wrestle everywhere” would have been irresistible to set for its first line alone, but its vision of a nameless rapture abroad in the world was rich in settable images, and Schuller didn’t miss one.

Millay’s heartbroken sonnet “Time does not bring relief” brought forth music that teetered between tender nostalgia and cries of protest. Stein’s teasing poem that almost made sense, “Why am I if I am,” came out languidly, in a sparse setting touched with dry wit. The wit had a macabre edge in cummings’s “Me up at does,” as Mackenzie drily uttered a poisoned mouse’s reproach to the poet.

The applause of the modest-sized audience for Singing Poems was prolonged through two returns of the ensemble to the stage, perhaps in hopes that the composer could hear it from wherever he was.

Rand Steiger’s Elliott’s Instruments, composed in 2010 for the 100th birthday of Elliott Carter, could be subtitled “A Fan’s Notes,” since Steiger admitted in a program note to being an unabashed admirer of the long-lived composer, attending every Carter premiere he could get to and incorporating allusions to twenty Carter chamber works in this birthday piece.

Because the works Steiger referenced were for the instruments in Collage New Music, the resulting musical collage gave each of the players his or her moment in the sun. Cellist Moerschel sang a cantabile solo over pointillistic piano; woodwinds fluttered as violinist French leaped in virtuoso double-stops; percussionist McNutt set the mood with gentle bells and marimba here, driving tom-toms there; pianist Oldfather bounded around the keyboard in a fiery cadenza. Conductor Hoose wrapped it all up nicely with a burst of energy for the whole group near the close.

Spotlighting individual players was also a feature of Schuller’s 1988 valentine to this ensemble, Bouquet for Collage, a collection of character pieces that functioned as micro-concertos for each instrument in the group. (Flutist Krueger and clarinetist Annis were allotted three movements each, since they doubled on the higher- and lower-pitched cousins of their main instruments.)

Schuller’s evident affection for this group was returned in full measure, as the players gave richly characterized performances of the movements with their whimsical, largely self-explanatory titles: “A Mellow Cello,” “Frolicking Fiddle,” “With Mallets Aforethought,” “Piccsyish” (for piccolo), and “Eine Kleine Ragtimemusik” (for piano), to name a few.

All the players performed with flair; especially striking was the remarkable range of Annis’s bass clarinet, from its singing high notes to its drainpipe lower register, in the movement titled “Darkly Somber.”

At the close of Bouquet for Collage, Hoose whipped up the group to a quick, explosive finish, a spurt of fireworks to cap an evening that had become not so much a memorial as a celebration.

The next performance of Collage New Music will be “Voices of Today and Tomorrow” with Dominique LaBelle, soprano, Jan. 10, 2016 at Pickman Hall, Longy School. collagenewmusic.org.

Posted in Performances