Bronfman, Nelsons tackle Bartók with a tribute to a BSO legend

Yefim Bronfman performed Bartok’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with Andris Nelsons and the BSO Tuesday night at Symphony Hall. Photo: Winslow Townson

Pianist Yefim Bronfman has been making the concert circuit rounds with Bartók’s piano concertos, works that demand substantial technical facility from the soloist, even to the point of bloody fingers. Indeed, one doesn’t need to look hard to find the photograph of a bloody keyboard after Bronfman’s performance of Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra early this fall, which has become an internet meme.

Bronfman is a spectacular artist with a no-nonsense demeanor, commanding a crystalline technique at the instrument while keeping a close eye to the musical line.

That was the case Tuesday night at Symphony Hall, where Bronfman performed Bartók’s Second Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, led by Andris Nelsons.

Bartók’s concerto is cast in a five-part arch form that spans three movements, which contains a propulsive rhythmic drive and earthshaking passages for the piano that make the work a true showpiece.

Bronfman brought the full Bartók, handling the percussive and angular phrases that comprise the outer movements with creamy tone that blurred the music into a wash of sound. The pianist’s approach to Bartók’s gnarly writing is largely melodic, and he took care to shape the phrases into long arcs where appropriate.

Nelsons coaxed stern and fiery playing from the winds and percussion in the first movement to build thick stacks of harmonies. In the mysterious second movement, the strings covered Bronfman’s line in a thin veil of sound, and the pianist gave spacious treatment to the sparsely written piano part. The middle section was powerful in its whirlwind of piano figures.

The final movement was electrifying with pianist and orchestra engaged in a furious tradeoff of the driving phrases, the music gradually building in intensity.

Rapturous applause brought Bronfman back onstage for an encore, a tender and silver-laced rendition of the Romanze from Schumann’s Faschingsschwank aus Wien.

Preceding the concerto was Haydn’s Symphony No. 30 in C.

Nicknamed the “Alleluia” because of its quotation of a Gregorian chant melody, this early work of Haydn’s, as Jan Swafford pointed out in his richly written program note, is more festive than expressive. Full of sprightly melodies, the three movements of this symphony show a composer in the early stages of his development with the genre.

Nelsons led a technicolor performance that highlighted the details of the score that often go unnoticed, such as the chugging bass line and occasional horn call. His broad approach sometimes led to some tentative ensemble attacks, but this performance was an overall delight. The first movement was full of effervescent energy while the lines of the second seemed to trickle in the casual tempo. The minuet finale moved at a stately pace with Nelsons coaxing the phrases into a graceful, dancing lilt.

After intermission, Nelsons led a similarly rich performance of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1 in G minor. Titled “Winter Daydreams,” is a cheerful affair when compared to the tragedy-laced works he would later write.

Nelsons’ reading was awash in bold colors that drew out the broad details of the score that, as in the Haydn, highlighted aspects of the music not usually heard, such as the agitated string passages in the first movement, the wayward horn calls of the third, and the brass passages in the fourth.

Nelsons’ affinity for the big picture sometimes glossed over the finer details of the score. The bristly statements of the first movement, for example, could have used more bite.

The conductor, though, excels at slow movements, and the prominent Russian-flavored theme of the second was full of lush sounds, initiated by John Ferrillo’s sweet-toned oboe solo.

The scherzo moved at a brisk pace, with the music sounding light on its feet, while the waltzing theme central to the movement crested and broke like waves.

After crafting the nebulous phrases that open the fourth movement into a shimmering tapestry, Nelsons led a spirited reading of the coda to bring to symphony and the concert to a rousing conclusion.

- ________________

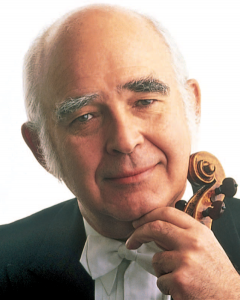

The concert opened with a beautiful, singing performance of Bach’s “Air on a G string,” played in memory of Joseph Silverstein, the former longtime concertmaster and assistant conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra who died suddenly this past Saturday at the age of 83.

Silverstein joined the BSO violin section in 1955 as its youngest member and went on to serve with the orchestra until 1984, a stint that included twenty-two years as concertmaster (1962-1984) and thirteen as assistant conductor (1971-1984).

While in Boston, he was a founding member of the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, and served as the ensemble’s artistic director. Following his work with the BSO, Silverstein went on to become music director of the Utah Symphony Orchestra, a position he held from 1983 to 1998.

Silverstein was also a dedicated teacher and taught at the Tanglewood Music Center, The New England Conservatory, Boston University, Yale University, and the Curtis Institute of Music. Many of his students now perform as part of the string sections of the BSO and other leading orchestras.

He is survived by his wife, Adrienne, daughters Bunny and Deborah, a son Marc, and four grandchildren. A public memorial for Silverstein will be held in the spring.

The program will be repeated 1:30 p.m. Friday and 8 p.m. Saturday at Symphony Hall. bso.org; 888-266-1200

Posted in Performances