Fine singing lifts BLO’s feminist retooling of “Don Giovanni”

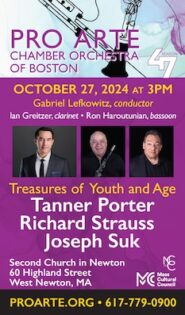

Jennifer Johnson Cano and Duncan Rock in Boston Lyric Opera’s production of Mozart’s “Don Giovanni.” Photo: Charles Erickson

It always was about the women, anyway.

Boston Lyric Opera’s new production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, which opened Friday night at the Shubert Theatre, came billboarded with a fierce-looking image of mezzo-soprano Jennifer Johnson Cano as Donna Elvira and heralded with publicity and interviews promising a kind of feminist Don for an era when date-rape is taken more seriously. And, to the extent that the frat-boy antics of the oversexed Don and his servant Leporello can be steered in that direction, Friday’s performance managed to do so—with a big helping hand from Wolfgang Amadeus.

It was Mozart himself who first saw more gold to be mined in the character of Donna Elvira, the Don’s relentless scourge (at first, anyway), and added a recitative and aria for her to the Vienna production that followed the Prague premiere. The current production, through score cuts and staging, moves further down that road, catering to an audience more likely to identify with Elvira’s assertiveness than with, say, Donna Anna’s more passive suffering.

Even without any idea what audiences would want in the 21st century, Mozart found more psychological interest in the dilemmas of the wronged women than in the single-minded male quest for sex (Giovanni), survival (Leporello), or revenge (everybody else), and his score reflects that.

Fortunately, this production has in Jennifer Johnson Cano a singer who lives up to her enhanced billing. No longer a mere scold and nuisance—as Don Giovanni, and some other productions, see her—Elvira took on new dimensions Friday night as Johnson Cano took full advantage of the musical resources Mozart provided, tailoring her clear, versatile voice from the spitting fury of her first rage aria “Ah! chi mi dice mai” to the excited ambivalence of “Ah, taci, ingiusto core” and the resigned forgiveness of “Mi tradì quell’alma ingrata.” Elvira is the only character in this drama who evolves noticeably during the action, and Johnson Cano, in an auspicious debut with this company, made sure the evolution was noticed.

So one wonders why stage director Emma Griffin felt the need also to literally “undo” this character visually. Elvira’s first entrance, in traveling attire and plumed hat, is like a battleship sailing onstage, its guns trained on Don Giovanni. With each subsequent entrance, the character loses some of her accoutrements and physical panache, until by the middle of Act II her hair is loose and tangled, and she is flopping around the stage in her voluminous red gown like a wounded bird. A point was being made, but what? That women who dare to be assertive should expect to end up pitiable and half-mad?

The confusion on this account arose not from another choice that was made, but from one that wasn’t. This production just sort of stipulated that Don Giovanni was irresistible to women, without proposing any reason why. Baritone Duncan Rock, at his first entrance in a sleeveless undershirt, looked not just well built but freakishly buff, and it was a relief when all those biceps and pecs and lats were stuffed into some clothes. Still, he might have parlayed all those muscles into a brutish, Stanley Kowalski sex appeal, but this production didn’t go there.

Instead, this Don came off as a fairly likable party animal with a violent temper and some tendency to preen—hardly major turn-ons for women, one would think. In his BLO debut, singer Rock at least made him vocally convincing, with a powerful, focused baritone brimming with masculine energy, which he throttled back to a seductive pianissimo in his serenade “Deh, vieni alla finestra.”

In fact, singing was the strong suit of this production from top to bottom. And there wasn’t much of a bottom, since Mozart gave each character in the small cast at least one moment to shine. And when he, and this production, put them together in ensembles of two all the way up to seven, the joy multiplied accordingly.

Soprano Meredith Hansen was vocally and physically steadfast as Donna Anna, the conscience of the drama, and managed well in the taxing coloratura of her aria “Forse, forse.” Another puzzling choice, perhaps ripped from today’s headlines, was to change the action in the first scene from Anna bravely attempting to arrest Giovanni for his unseen assault on her to Anna being forcibly undressed by the rake (while she perplexingly repeats “I won’t let you run away”!).

In an amiable performance as the peasant girl Zerlina, soprano Chelsea Basler suffered a bit from having some of the gumption trimmed out of her part, leaving her to project a little flirtiness and a little vulnerability in an attractive if not powerful voice.

These characters’ would-be bridegrooms were well enacted by John Bellemer as Don Ottavio and bass-baritone David Cushing as Masetto. Bellemer sang in a forthright, good-guy tenor as the slightly clueless nobleman, moving in a strikingly natural way onstage while other characters struck poses around him. Cushing’s robust bass-baritone and rough manners suited the country boy who wasn’t going to let anybody push him around, and did anyway.

The character Leporello is a show-stealer, and bass Kevin Burdette managed the heist in style, whether mouthing off at his master in their buddy scenes, imitating the boss’s walk and voice in the disguise scene, or just trying not to get too seriously injured when another of the Don’s schemes goes awry. His comic timing and wide-ranging basso buffo made him an audience favorite.

Looming over all was bass Steven Humes as the Commendatore, the statue that came to dinner. At his big moment as the agent of Giovanni’s fate, his voice had a bit of croak in it, either an inherent quality or cultivated for the role, that suited this ghostly presence.

Conductor David Angus and the BLO Orchestra gave a spooky, then lively, account of the overture, and kept the action moving thereafter. Mozart’s many felicities of scoring were present without distracting attention from the singers. Donna Anna may have been hesitant to marry Don Ottavio, but soprano Hansen as Anna definitely had a good thing going with the orchestra’s woodwind section.

In its brief appearances the BLO Chorus, under chorusmaster Michelle Alexander, sang well and provided a welcome opening-up of this otherwise slightly claustrophobic production.

Laura Jellinek’s sparsely furnished set and Tilly Grimes’s opulent costumes followed a time-bending concept, with modern art in an 18th-century room, the peasant characters in sneakers and jeans jackets and the Don’s party guests in full Marie Antoinette finery and masks, as if going to the carnival in Venice. (Forget about Seville in 1670, the location specified in the libretto.) It all seemed a good visual analogue to hearing 18th-century music in the 21st, but if the designers were sending a message other than that, it eluded this listener.

Mark Barton’s lighting did well at creating states of mind to substitute for the various gardens, cemeteries, balconies and ballrooms that were sacrificed to this production’s one-set concept. A few sudden-spotlight cues seemed more effect-y than effective, as was the red wash on the back wall when the characters were pointing accusing fingers at Giovanni (flames, get it?), but the responsibility for these belongs with director Griffin.

This performance ended with the Don’s demise, omitting the other characters’ “resolution” ensemble that follows. Mozart himself authorized productions with and without those final pages, the debate about them continues, and this review is long enough already. Suffice it to say that, in this musically excellent and conceptually perplexing production, the carnival masks turned demonic at the end, and in the flameless finale one horned female demon found a poetically just way to send the horny Don to his reward—call it “fatal attraction.”

Don Giovanni will be repeated 3 p.m. Sunday and May 10, and 7:30 p.m. Wednesday and Friday. blo.org; 617-542-6772.

Posted in Performances