Longy Opera offers a delightful double bill of Ravel and Weill

With new opera companies springing up in Boston these days, it is sometimes easy to neglect the fine work going on in the city’s music schools. The New England Conservatory gave solid performances of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea in February, and the NEC opera program recently staged Strauss’ Die Fledermaus. Boston University’s Opera Institute also offered Mozart’s Don Giovanni this month.

This weekend at Pickman Hall, Longy Conservatory’s own Opera Department performed a delightful double bill of one-act operas. With a fine cast of young singers, Saturday night’s performance proved to be as entertaining and enriching as any show going on in the city.

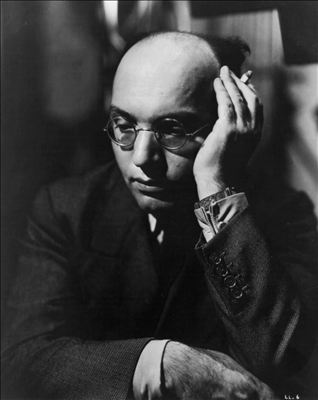

The opener, Kurt Weill’s folk opera Down in the Valley, tells the vexing story of Brack Weaver, an escaped convict from Birmingham Jail who is sentenced to death for the accidental murder of Thomas Bouché, a wealthy drunkard and would-be suitor to Weaver’s girlfriend, Jenny Parsons.

Originally conceived for radio in 1945, Down in the Valley is cast in a lyrical sing-song style, the same approach Copland would later mine in The Tender Land. Weill’s score includes American folk songs such as the title-bearing “Down in the Valley,” “The Lonesome Dove,” “The Little Black Train,” and “Sourwood Mountain,” among others.

Joshua Smith is Brack. Dressed in flannel shirt and jeans, he caught the down-home country-boy character to good effect. Though his faux spoken southern drawl was sometimes fitful, his singing voice, with its light shake and throaty tone, was well suited to the music’s folksy charm.

Jenny, played by Lauren Frick, is the daughter caught between the affections of two men. Frick possesses a resonant and ripe soprano that is even in all her registers. She delivered a tender account of “Brack Weaver, My True Love.”

Jenny’s father, a spoken role played by Gabriel Pang, forbids Jenny to go to the local dance with anyone except Thomas Bouché, the financier who says he may be able to extend her father’s credit. Pang’s youthful look and self-assured stage presence seemed an ill fit for the role. His tone and delivery made him come across as another of Jenny’s suitors rather than a stern and money-obsessed father.

Roger Sidebotham, on the other hand, with his slicked back hair and goatee beard, captured the archetypical trickster in Thomas Bouché. With the swagger of a drunkard, he sang a comical and slurred rendition of “Hop Up, My Ladies.”

The biggest problem in this performance was the inconsistent balance between singers and the orchestra. Smith had some trouble delivering his lines over the thick accompaniment, and Bennett Billard, cast as the charismatic country preacher, was drowned out almost entirely in the rousing “Little Black Train.”

The resonant, intimate space of Pickman Hall probably didn’t help matters, but the biggest reason for the balance issues may be Weill’s opera itself. Even though the opera was revised for stage in 1948, Weill’s orchestration remains thick and saturated with color, and singers are often left to belt their lines against the full blast of the instrumentation. When blended, however, the chorus and orchestra in Saturday’s performance sounded full and rich. The balancing issues apart, Geoffrey McDonald led the way with a firmly paced, sensitive, and detailed reading of the score.

Overall balance fared better in the second opera on the program, Ravel’s L’heure espagnole.

The delicious score, cast for five singers and chamber orchestra, is a tour de force. The vocal and instrumental parts are chock full of Spanish-laced virtuosic riffs and habanera rhythms.

The fifty-minute opera tells the Mozartesque story of a Toledo clockmaker’s wife, aptly named Concepción, who cavorts with three different men while her husband is at work. Ramiro, a mule driver who volunteers as a furniture mover, must carry grandfather clocks back and forth to Concepción’s private room. Little does he know that hiding in the clocks are two of her would-be lovers, the poet Gonsalve and banker Don Iñigo. But in the end the woman is drawn to Ramiro, who seems to never break a sweat carrying the heavy load.

As Concepción, Mio Hatanaka, dressed in sleek black dress, sang her solos with a rich velvety tone, capturing, to good effect, the woman’s coquettish nature.

Each of her lovers sang clearly and capably with a firm sense of the opera’s legato vocal style. They also proved effective actors and mined a sometimes cartoonish comedy from this lusty story.

As Ramiro, Ethan Sagin, clad in black shirt, leather jacket, and shades, looked less a mule driver than Fonzie’s younger brother from Happy Days. Smitten with Concepción, he showed off his strength by doing arm curls with a giant candelabra and performing squats while holding the clockmaker’s desk, all while singing affectionately.

Cornelius David, as Gonsalve, elicited the most laughter as he pranced around the stage dressed as a ballerina. Nicholas Dankner, dressed in a business suit, was fittingly cocky as the banker Don Iñigo. And in his brief role as the clockmaker Torquemada, Brian Minnick made for an appropriately clueless and, later, jealous husband.

The finest singing of the evening came in the opera’s concluding quintet. Here, the singers broke character to relay the moral of the story (every dog, or mule driver, has his day) while handling the trills, shakes, and burbling vocalise with dexterity.

The props were minimal but effective: large black boxes served as grandfather clocks, and the space was otherwise decorated with simple tables and chairs.

Here too, Geoffrey McDonald led with clear direction of Ravel’s score. The chamber orchestra answered his deliberate gestures with intensity and flair.

Geoffrey McDonald will conduct the Longy Conservatory Orchestra in music by Weber, Wagner, Franck, Debussy, and Milhaud 8 p.m. May 16 at Pickman Hall. longy.edu.

Posted in Performances