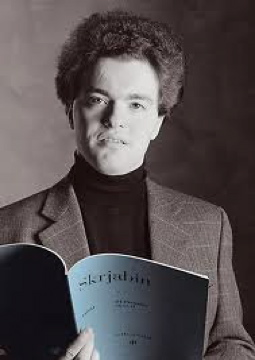

Kissin delivers the Romantic thunder for the Celebrity Series

After Evgeny Kissin’s piano recital Sunday afternoon, presented by Celebrity Series of Boston, one thing was sure: Nobody does turbulent like Alexander Scriabin, and nobody does turbulent Scriabin like Evgeny Kissin.

Without a hint of showiness—other than the spectacle of a great athlete in his prime—Kissin made a Scriabin sonata and several Scriabin etudes rumble, roar, and then seemingly overflow the stage. When he closed the program with the crushing final chords of the famous Etude in C-sharp minor, Op. 8, No. 12, the capacity Symphony Hall audience, having received what it came to hear in ample measure, bounded to its feet and cheered.

No doubt Kissin could play entire programs of that kind of repertoire, and his fans would be happy. To his credit, the former child prodigy—still cherubic-looking at 42—continues to venture outside his Romantic comfort zone, and not in the way of the virtuosos of old, who would treat a Haydn sonata as a little warm-up exercise before the main event.

For one thing, Schubert’s Sonata in D major, D. 850, which occupied the entire first half of Sunday’s program, is just too big to ignore. It might seem that a composer born a mere 14 years before Liszt would not be such a stretch for a Romantic specialist, and pianists know that Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy influenced Liszt’s B minor Sonata, and so on. But in the end Schubert is not the first Romantic composer, he’s the last Viennese Classical composer.

Watching Kissin play a Schubert sonata was like watching a thoroughbred racehorse in a dressage competition. He can smell the backstretch, his large muscles twitch for it, and meanwhile they’re making him do all these little fussy motions.

Oddly, during the sonata’s opening bars–fast and loud to be sure, but made up of sharply delineated gestures set in contrast to each other, in the Classical style—Kissin rocked back and forth on the bench and shook his locks like Paderewski playing Liebestraum. Later, when playing music one could actually imagine rocking and shaking to, he was all stillness and composure on the bench, directing his energy into the music.

In the Schubert it seemed as though he was trying to coax some kind of a Romantic long line out of music that didn’t work that way. Busy fingers burbled and boomed, but the meaning of it all never was clear.

The second movement unfolds in its own sweet time, but Kissin rushed and foreshortened the rhythm, apparently from anxiety the movement would seem too long. Of course, few things sound longer than a Schubert slow movement played out of time.

Similarly, hurrying and blurring the syncopated rhythm of the scherzo took away its character as a bracing interlude between two subtle movements.

The little tick-tock nursery theme of the finale balances on the edge between naïveté and irony, foreign territory to the Romantic sensibility and apparently to this pianist’s as well. The rondo’s episodes seem to tumble out of a very assorted box of toys; their charm is in their difference from each other, but Kissin’s interpretation seemed bent on unifying everything into one smooth, rather featureless piece. The last tick-tocks of the coda were sentimentalized in a haze of damper-pedal reverb—a defensible choice, but no more satisfying than the rest of the performance.

Scriabin scrupulously titled his Sonata No. 2 in G-sharp minor, Op. 19, a “Sonata-Fantasy” because it’s in two movements, neither one in “sonata form.” The work appears fairly often on recital programs, especially by Russian-trained pianists, probably more because of its exciting, etude-like finale than its somewhat elusive first movement.

According to the composer, the sonata depicts moods of the sea, and on Sunday Kissin took to its breadths and depths with almost palpable relief. The first movement’s waters seemed deep and luminous under his fingers, and, as mentioned, the storm surged and howled impressively in the finale.

Scriabin’s 12 Etudes, Op. 8, were composed in emulation of similar sets by Chopin, but the young Russian composer piled on difficulties the Polish master never dreamed of. Kissin led off with etudes Nos. 2 and 4 of the set, studies in clashes of irregular note groups, the first tumultuous and the other bubbling happily like a Chopin impromptu; defying the rhythmic complications, Kissin played both with delicious abandon.

The remaining five etudes in Sunday’s selection included, besides the climactic No. 12, two intricate studies in octaves (Nos. 5 and 9) and two slow, singing pieces whose challenges were in the polyphonic accompaniment (No. 4 and No. 11)—a varied assortment, each vividly characterized.

Kissin made the audience work for their encores, but after three leisurely returns to the stage he relented with Bach’s Siciliano from the Flute Sonata in E-flat, BWV 1031, arranged by Wilhelm Kempff, and sounding on this occasion more like an organ transcription than a flute piece; Scriabin’s Etude in C-sharp minor, Op. 42, No. 5, another splendid rumble-and-roar with approximately eleven million notes; and an all-stops-out rendition of Chopin’s Polonaise in A-flat major, Op. 53.

The Celebrity Series of Boston presents the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Zubin Mehta at Symphony Hall, 8 p.m. Wednesday. celebrityseries.org; 617-482-6661.

Posted in Performances

Posted Mar 17, 2014 at 11:52 pm by Chaim Gogol

In my opinion this review reflects a thorough misunderstanding of the Schubert D major Sonata on the part of the reviewer. For example, the comment about Kissin’s treatment of rhythm in the second movement is simply factually untrue. This was one of the very few performances I have heard in which the orchestral ambitions of the writing were fully achieved.

Posted Mar 18, 2014 at 2:00 am by Luisa Guembes

This review seems a bit ” personal” not informed.

A bit below the belt…… Envy?