Emmanuel Music’s Beethoven program offers a double triple with singers and concerto

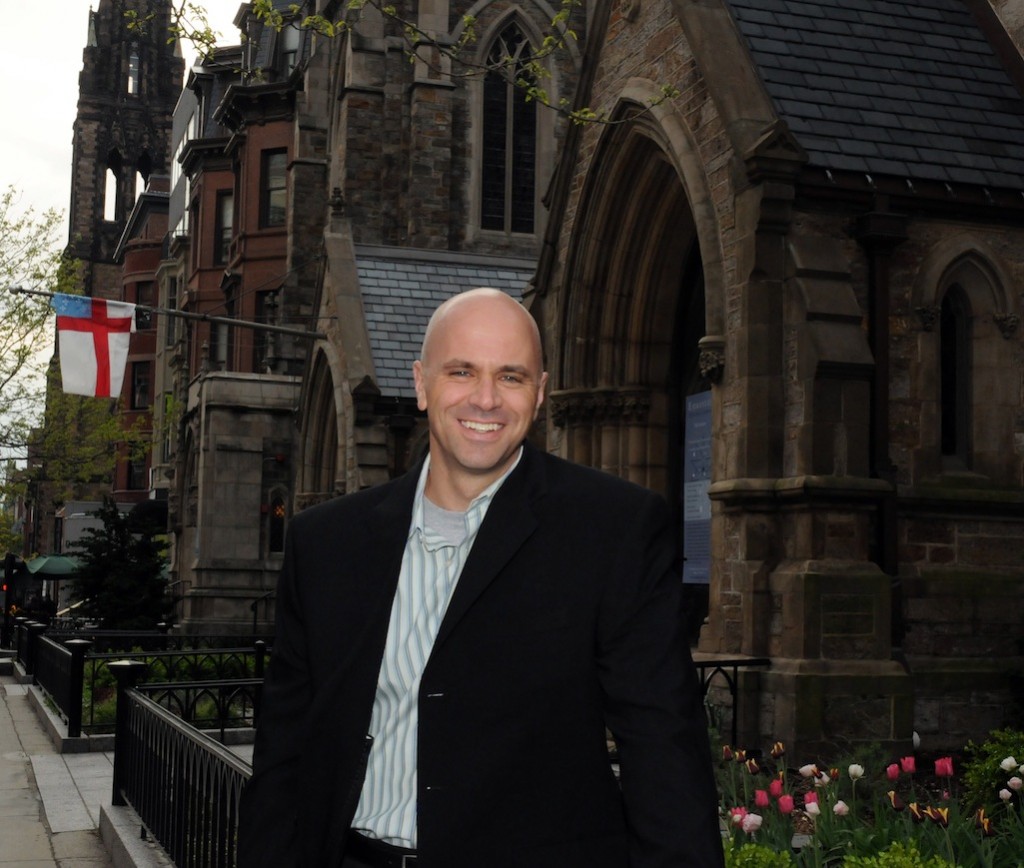

Ryan Turner led Emmanuel Music in a Beethoven program Saturday night.

In a program that hinted at the lyric sweep of Beethoven, and showed some of his heroic drama as well, Emmanuel Music, under the direction of Ryan Turner, opened its season Saturday evening at Emmanuel Church in the Back Bay.

Emmanuel has a long running Beethoven chamber series, which continues later this fall. In this program, Turner ventured orchestral settings, including some concert arias.

He opened with the Egmont Overture, the Mozart-sized orchestra alert and brisk, if not overwhelming in impact. There was vigorous and tuneful playing by the brass and winds, which melded into the ensemble rather than standing out. Still, the reading was crisp and appropriate to the drama of the setting.

A handful of concert arias followed, with soprano Susan Consoli, tenor Charles Blandy and baritone Paul Max Tipton alternating as soloists and trio. All have lyric skills, and showed a keen awareness of text and mood. Blandy’s solo O Welch ein Leben could have benefited from more precise orchestral accompaniment, yet Tipton sang delightfully and strong in his comic turn, Mit Mädeln sich vertragen.

Of the aria set, Consoli brought Italian intensity to the theatrical Ah! Perfido. After the recitative introduction, setting the scene of the faithless lover’s betrayal, a gentle melody (introduced delicately by clarinet) eases into the heroine’s anger: he may no longer love her, but can he at least pity her? Consoli sang with scorned emotion, and the orchestra responded with alert accompaniment. A pizzicato break at the lines “I will die of grief” added a certain tender counterpoint to Consoli’s flashing vocal anger.

Three distinguished players from Boston’s talented musical pool joined the orchestra after intermission for Beethoven’s Triple Concerto: the renowned Mozart keyboard specialist Robert Levin, cellist Rafael Popper-Keizer, and violinist Heather Braun. The trio worked hard to capture Beethoven’s spirit of modest virtuosity, infused with heightened trio interaction.

Braun stood up front, with Popper-Keizer seated to her side. In the midst of the crowded stage, Levin sat behind the conductor, facing the audience, with the lid off the piano. The sound they produced was a curiosity in itself: Braun had the easiest time of it, above the fray. Popper-Keizer sometimes got lost in the wash of instruments, but Levin, barely in view but seated almost directed under the arch, boomed invisibly away.

Turner worked expertly at balancing the sonic acrobatics, and mostly it worked.The concerto is a real trio work, with solo virtuosity replaced with blended duets, overlapped lines, unison playing or direct repeats passed verbatim among the soloists.

The middle Largo showed the most complete execution. The cello line opened vibrantly, calling out alone until the melody was fully understood. The solo strings dominated the slow movement, with Levin working as support, the orchestra quietly accenting. The attacca jump to the final movement brought back the chaos of sound, balancing out the dancing duple rhythm. But for that central introspective section, the lyric intent of the entire program came to life.

Posted in Performances