Britten’s unsettling parable comes richly across with Intermezzo’s “Prodigal Son”

Intermezzo, the New England Chamber Opera series, presented Benjamin Britten’s The Prodigal Son Friday night in Cambridge. Marking the British composer’s centennial, this was the first Boston performance of the opera in over 30 years.

The Prodigal Son was the third of the relatively short “parables for church performances” that Britten wrote in the 1960s. These three operas plumbed the bible for stories, but used these stories as springboards for exploring archetypal stories and highly ritualized forms of theatre, inspired by Japanese Noh drama. The results are sometimes difficult for audiences, but as with Intermezzo’s performance last night at First Church Cambridge, also deeply rewarding.

On the surface, The Prodigal Son follows the well-known biblical parable: a young man, the younger son of two, asks his father for his share of his inheritance. The father acquiesces, and the younger son leaves for the city, where he squanders his money through extravagance. Desperate and abject, the younger son returns to his father, who readily welcomes his son back and orders a feast. This irks the elder son, who has been working diligently on his father’s farm, and who does not see why his brother should be rewarded for his profligance. The father’s famous reply is that the younger brother, once dead, is alive again; once lost, has now been found.

Though the biblical parable is famous for its commentary on divine forgiveness, Britten’s opera has a different focus, instigated by his addition of the character of the Tempter. First portrayed by Britten’s lover, Peter Pears, and played here in a standout performance by Jason McStoots—whose tone eerily recalls that of Pears—the character of the Tempter falls in the tradition of Milton’s Satan. It is he who has the first words in the opera, announcing his determination to destroy the family’s harmony by tempting the younger son, and who subsequently sets the plot in action.

Hearing McStoots’s Tempter, who negotiates insinuating glissandos and pagan-sounding melismas with aplomb, one can’t help feeling that Britten had much more sympathy for the deviant Tempter than for the stolid biblical family. This is underscored by the stacked dissonances Britten has the chorus of family servants sing: hardly a welcoming or homely sort of aural effect.

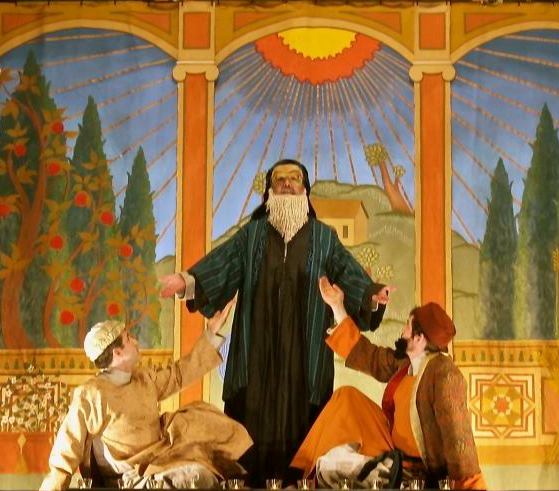

Intermezzo’s production reflects the imbalances in Britten’s score. The original production drew heavily on Japanese Noh theatre, featuring masks and heavily stylized gestures. The production last night was faithful to the original, with the Tempter and the father wearing masks; however, one feels that these are the two characters who least need them. It is the younger and older sons, whose discontent and jealousy are so eminently human, that require masks in order to step into the realm of the archetypal in which Britten’s score functions.

McStoots’s Tempter was the most dynamic singer of the night, but the three other soloists gave superb perfomrnaces. Paul Guttry brought patrician gravity to the father, and David McFerrin’s baritone captured the older son’s diligent and resentful character. Matthew DiBattista’s warm tenor embodied the younger son’s innocence, and his subsequent despair was poignantly conveyed.

Praise is also deserving for Edward Jones’s taut conducting and the Intermezzo orchestra. First Church Cambridge’s romanesque arches were an excellent setting for Britten’s opera. Lastly, the young chorus of acolytes deserved praise. Their shift from the voices of temptresses to the voices of hungry children was one of the most unsettling moments in an opera whose secret purpose seemed to be that of unsettling the biblical parable.

The Prodigal Son will be repeated 8 p.m. Saturday at First Church Cambridge. intermezzo-opera.org.

Posted in Performances