Ludovico Ensemble brings an array of colors and rhythm to percussion program

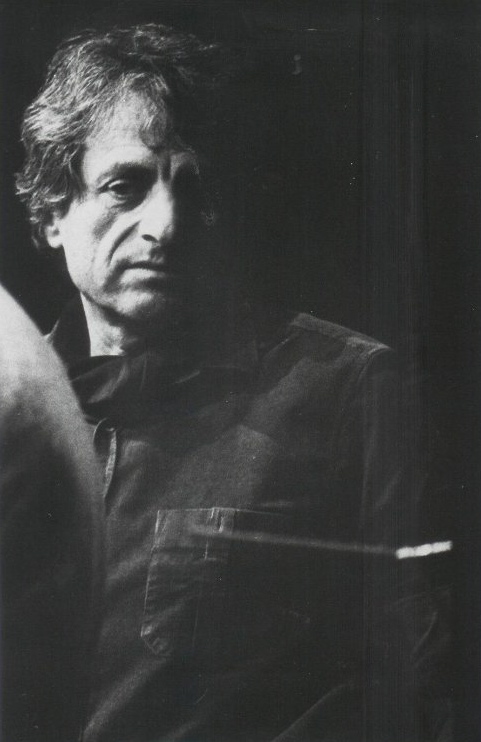

Iannis Xenakis’s “Okhu” was performed Wednesday night by the Ludovico Ensemble.

The canard that percussion programs are nothing but ceaseless rhythmic exercises, was put to rest by the Ludovico Ensemble Wednesday evening in Boston Conservatory’s Studio 401. The ensemble, founded by Nicholas Tolle and conducted in part of this program by Jeffrey Means, performed three widely varied works by Iannis Xenakis, Georges Aperghis, and Wolfgang Rihm.

Ensemble-in-residence at BoCo, in its ten years Ludovico has compiled an impressive archive of avant-garde performances. Like this evening’s program, many of the works have come from the core of European 20th-century musical elite: Kurtag, Schnittke, Schoenberg, Penderecki, and the like, and also includes commissioned works by Rudolf Rojahn, Lachlan Fife, Andy Vores and others.

Xenakis’ Okho is set for three djembe players. Written in 1989, by using African drums it represents Xenakis’ subversion of a commission for the bicentennial of the French Revolution (Born in Greece, the composer was a longtime French citizen). The djembe, a goblet shaped skin drum usually played by hand, creates unusual volume for its size (about two feet high, and a foot in diameter).

After an extended opening with unison syncopated patterns that were briefly developed, Okho grew into a much more complex exchange with extended techniques. Djembe playing is built around three sounds: bass, tone and slap, moving up the scale. Tolle, Means and Mike Williams explored all three, but added extended finger techniques (knuckles, glissando) and for a brief but interesting section played both slap and stick, with each player employing one mallet.

Georges Aperghis’ Les guetteurs de sons (Watchers of sounds) is a performance art piece for percussionists. Three players (Means, Tolle, Williams) sit in a semi-circle so they can see each other and face the audience as well. They each have a floor-pedaled bass, and a tom-tom for their hands. Aperghis’ fanciful “text” that accompanies the work continually references silence, and surprise, and the players “act” this out, frequently raising their hands as if to strike the drums, but then stopping without sound at the drumhead. Sometimes they bend over and listen to the skin, as if to discern the absent sound. When they do play the sound is intermittent, delicate. The drummers offer guttural voicings, or barely audible French phrases, but mostly just listen.

As does the audience. Like Cage’s silent works, Les guetteurs de sons becomes as much about what you want to hear as what you hear. While the players mime playing, the sounds of the room, the electronic feed of the lights, the noises outside, all come alive as part of the music. When the players actually strike the drums, or gently pedal the basses, mixing the ambient sound into the performed sound becomes the audience’s new task. The piece works incredibly well for what some might view as its inherent lack of musical “substance.”

Wolfgang Rihm’s Tutuguri VI is more of a drumming work than percussion. Set for five players (Aaron Trant, Robert Schulz and Ross Karre joining Tolle and Williams with Means conducting), each manning a large kit of drums but very little metal percussion, the work is expansive at more than half an hour and voluminous in sound and ideas.

Rihm found great inspiration in the works of Antonin Artaud, the 20th-century absurdist French playwright and poet whose philosophy was much more influential than his actual works. His concept of the “theater of cruelty” had particular impact. Tutuguri was the title of several works that explored Artaud’s peyote-laced experiences with the Tarahumara people in Mexico, and Rihm transformed his experiences into this work and an even larger version for percussion and recorded chorus.

This drumming work explores simple, repeated rhythmic patterns, and in almost no way explores the tonal variety of the percussion palette. Phrases begin in unison, slowly, then accelerate and decelerate. They are almost all unison, and episodic—no long lines here. In fact, hardly any ideas are repeated. One rhythmic pattern stops, another begins, it stops, then another. After a while it’s like a journey into a constantly changing countryside.

The playing, even though there seemed to be many extraneous notes, was exceptional. The work’s “climax” is one of utter simplicity, the players almost stopping in a slow two-hand pattern that becomes one handed and then halts. At the end, they finally pick up cymbals and play a splashing short set, washing the room in colors that have been previously absent.

Posted in Performances