Savall offers a diverse Terpsichorean journey for Boston Early Music Festival

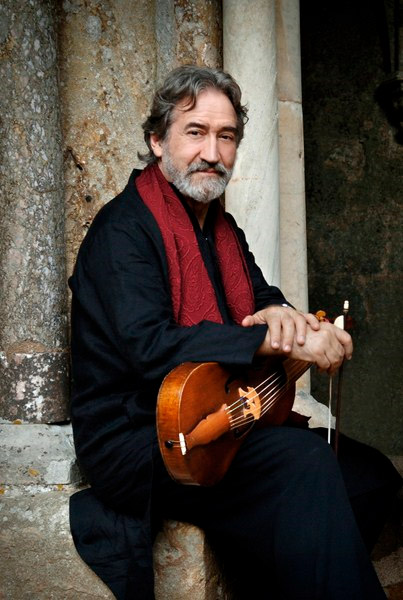

Jordi Savall and Hesperion XXI performed Friday night at Jordan Hall.

Jordi Savall’s performance with Hesperion XXI for the Boston Early Music Festival Friday evening at Jordan Hall had all the trappings of a rock concert. There were no “Golden Age of Consort Viol Music” tour T-shirts. But everything else was there.

There was the packed house, the swarms of fans at the CD table, the insider conversations at intermission—“He still looks great” and “I like the old percussionist better.” And the roaring ovations at the end, and insistence on encores—even a call-out for some favorites.

It’s an unusual display for a treble viol player and the ensemble he created almost forty years ago, with a small group of fellows from the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis in Basel, where they were studying early performance practices and wanted to bring the music back to life.

Much has changed for Savall since then. His original ensemble has dispersed, his wife and collaborator, the luminous soprano Montserrat Figueras, died last year. Lutenist Hopkinson Smith and flutist Lorenzo Alpert left the group long ago.

But the goal—to bring early music to life—still gets achieved magnificently. Joined by a sextet of players, Savall explored two centuries—the sixteenth and seventeenth—of viol music, moving buoyantly through the national styles of Italy, England, Spain, France and Germany like a band of jongleurs.

Contemporary audiences who see the string quartet as a kind of Socratic discourse among upper, middle and lower voices will recognize the same sonic world in the viol consort—with a Renaissance twist. Savall played a treble instrument, and dominated the solo moments. He was accompanied by a trio of bass viols (Carol Lewis, Philippe Pierlot and Xavier Puertas, doubling on treble), Sergi Casademunt on tenor viol, Xavier Diaz-Latorre on viheuela and theorbo, and percussionist David Mayoral.

Each of the national sets followed what in Spanish is called the trattado tradition—incorporating popular songs into stylized dance movements, sometimes into short ballets.

The opening Italian group laid out the approach: a pavane, a galliard, perhaps a fantasia or romanesca thrown in, and then an improvisation based on a “Folie,” or crazed dance. The introductory set sounded stately and smooth, but the succeeding English songs, with familiar music drawn mainly from John Dowland’s songbook Lachrimae or Seven Teares, beginning with an almost mournful unison work and stepping through a series on alternating tempos, showed more diversity.

The Spanish grouping formed the centerpiece. Pivoting around works by Diego Ortiz and Antonio de Cabezon, the expressive range of the septet became more apparent. For most of the evening is was unclear why Savall employed three bass instruments: they played in unison, and never soloed, simply anchoring the rhythm with Mayoral. In these songs, especially Ortiz’ martial La Spagna, the volume of low tone completed the effect, with Savall and Diaz-Latorre, playing the guitar-like viheula for these songs, floating over the top.

A duel of a duet, Galliard Battaglia, from the German composer Samuel Scheidt, with Savall and Puertas flashing alternate lyrical lines on treble over basso continuo, proved the most vivd work after intermission. Among the oddities offered from the nearly thirty works was a French ballet, Les Ameriquains, a manuscript dating from 1621, a quirky allegory of the New World’s value to its conquerors.

Encores from William Brade (Scottish dance) and a French bourrée completed the enjoyable and insightful presentation.

The Boston Early Music Festival will present Monteverdi’s Orfeo November 24 and 25. bemf.org

Posted in Performances