Pianist Trifonov inaugurates Longy series with captivating mastery

Friday night’s piano recital by Daniil Trifonov was a double debut: the first appearance in Boston by the 21-year-old Russian phenomenon, and the first presentation at Pickman Hall by the venerable Celebrity Series of Boston.

Both may be said to have achieved triumph on a small scale. If Trifonov is not quite the Next Big Thing of the piano—at least not yet—the shy, floppy-haired youngster from Nizhny Novgorod has a big talent and a winning presence at the instrument, and he captivated Friday’s audience.

The 280-seat, birch-paneled, award-winning venue—the full name of which is Pickman Hall at the Longy School of Music of Bard College—was looking much younger than its 42 years, and proved a most agreeable, intimate place to hear music.

It must be said that, in this cufflink box of a hall, the nine-foot Steinway grand onstage looked about 25 feet long. Thoughts of being enclosed in this small space with one of those piano-splintering Russian giants such as Richter or Berman brought trepidation, but in the end fears of hearing damage were not realized, as Trifonov’s youthful enthusiasms did not include ear-battering.

His program played to the strengths of the Russian school: 20th-century Russian Romantics (Scriabin, Medtner, Stravinsky’s Firebird) in the first half, Debussy and Chopin after intermission.

As the Scriabin Sonata No. 3 began, there seemed to be little to distinguish Trifonov’s playing from that of dozens of other aspiring virtuosi in conservatories across the world. The technical facility was there in abundance, but so were the common faults: a sound that went somewhat harsh in forte and fuzzy in piano, and a limited range of tone color.

Gradually, however, one became aware of an uncommon sense of timing and malleable phrasing in Trifonov’s playing. He seemed to identify completely with Scriabin’s surging, feverish inspiration, and it made one want to go there with him. That is an element of musical communication that some artists never achieve, however brilliantly they illuminate Scriabin’s dense counterpoint, and it was something to treasure in this performance.

Lacking a real singing tone, Trifonov could go only so far in sculpting Scriabin’s intertwining melodies or projecting the Adagio’s lyrical theme, but he generated plenty of visceral excitement with fistfuls of octaves in the finale.

It usually requires a Russian visitor to bring us the music of Nikolai Karlovich Medtner, whose elaborate, fantastic piano style is something of a national taste. “Fairy tales” is a rather Disneyish translation for the title of Medtner’s wild, even bizarre character pieces—the German word Märchen suits them better—but there was nothing airy-fairy about Trifonov’s rendering of three of them, a diverse assortment that was moody, dazzling, and passionate by turns, concluding with pages of stupendous music that seemed to require three or four hands to play.

In the piano repertoire, Guido Agosti’s Three Excerpts from The Firebird plays a similar (if less frequently performed) role to Stravinsky’s own arrangement, Three Movements from Petrushka. But while the latter was conceived as purely a piano piece, Agosti’s rendering is a full-bore orchestral transcription, and Trifonov dipped as deeply as he could into the tone-color pot to reproduce the wild brass and percussion of Kastchei’s Infernal Dance, the trembling strings and mournful English horn of the Berceuse, and the all-out blazing tutti of the finale.

After such exertions, the economical brushstrokes of Debussy’s Images, Book I came as a relief to the ear, and as a test of interpretation emphasizing sensitivity over athleticism. Trifonov led with his strengths–fine phrasing and a sense of the long line—and took the first piece, “Reflets dans l’eau,” a little faster than usual, adding a touch of flow to Debussy’s deep pool and pinging droplets.

The decorous dance of “Hommage à Rameau” moved quite naturally to its fortissimo climaxes, and in realizing Debussy’s layered sonorities the pianist continued to find new resources of tone color. He brought a Russian sense of bizarre humor to “Mouvement,” smiling with delight as he evoked the runaway machine with softly whirring triplets, sudden exclamations, and an enigmatic close.

One expects that the so-called “Aeolian Harp” Etude, the first of Chopin’s Twelve Etudes, Op. 25, will be the lightest of confections, its rapid arpeggios seemingly floating in the air, and so it was on Friday night. But one wasn’t prepared to hear a pianist adopt that interpretation for most of the pieces in the set.

Chopin’s etudes, which he collected in two sets of twelve, are so notorious for the challenges they present to a pianist’s technique that watching a performance of one of the sets is usually like being a spectator at the Olympic decathlon, marveling at a display of strength, speed, and stamina. Trifonov, however, seemed not just to master the difficulties of these pieces, but to ignore them entirely, treating each one as if it were just a tuneful little prelude that happened to have a lot of notes. His playing was all about lightness, speed, and fantasy, humorous one moment and lyrical the next. (Of course he had to dig deeper for the drama of the great Lento, No. 7 in C-sharp minor.)

All that changed abruptly in the formidable last three etudes, nicknamed Octaves, Winter Wind, and Ocean. Trifonov put the pedal down and churned through No. 10’s double octaves in a barbaric roar, the better to set off the plaintive tenderness of the etude’s middle section. The keening wind of No. 11 seemed ready to blow the house down, but a kind of serenity settled over the pianist as the waves of arpeggios surged over the keyboard in No. 12. At the height of the storm, he broke into that open-mouthed smile, like an athlete exulting in his strength.

As encores, Trifonov offered charming and elegant performances of Liszt’s transcription of the Schumann song Widmung, Chopin’s Grande Valse brillante in E-flat, Op. 18, and Rachmaninoff’s transcription of the Gavotte from Bach’s Violin Partita in E major.

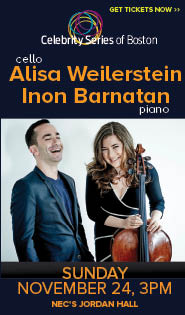

The next classical-music event of the Celebrity Series of Boston is the Pacifica String Quartet and clarinetist Anthony McGill at Pickman Hall, 8 p.m. Oct. 24. celebrityseries.org; 617-482-2595.

Posted in Performances