Intermezzo serves up a compelling American triptych of one-act divas

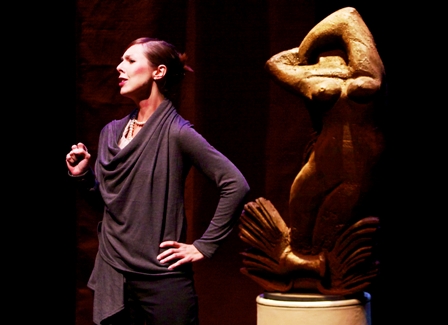

Kristen Watson in Jake Heggie's "At the Statue of Venus," presented Saturday by Intermezzo. Photo: Julius Ahn

Intermezzo, the New England Chamber Opera series, marked its tenth season by presenting a fresh program of rarely-heard American operas at the recently renovated Modern Theatre at Suffolk University Saturday night.

Billed as “The Diva Monologues” (admittedly a “bad variation” of The Vagina Monologues, said artistic director John Whittlesey), the program included three one-act psychological monodramas with female leads, a sequel to the company’s “Boys Night Out” production from last year.

The theme of love ties the three pieces together, commented director Kirsten Cairns in a pre-concert talk. The first character, full of nervous energy, is looking for love; the second is fearful of losing it; the third spends her long life reeling over love that was lost.

Jake Heggie’s At The Statue of Venus (2005), a witty soliloquy for soprano and piano, served as the opener. Terrence McNally’s libretto tells of Rose, a middle- aged woman anxiously awaiting her blind date by a statue of Venus in a museum. While waiting, thoughts race through her head. She worries about the appropriateness of her dress to the point of self deprecation (she is wearing black slacks for the date, a fact she references as a sort of punch line throughout the drama). Rose is equally concerned about her age and looks, frequently comparing herself to other women in the museum. In anticipation, she wonders what her date will look like and judges men walking her way: one, she notes, is bald and unattractive; another is strikingly handsome. And another approaches her to ask directions to the bathroom.

Heggie’s colorful score possesses elements of lyricism and American neoclassicism: crisp, rhythmic piano lines, and shifting meters highlight Rose’s nervousness.

Early in the performance, the pianist Linda Osborn overpowered soprano Kristen Watson on a few occasions. Watson’s voice, too, lost some volume and power at times while acting the part, as when she sang directly to the Venus statue placed at center stage. But the performance seemed to grow stronger as it progressed. Watson handled the coloratura lines with ease and was equally effective in bringing out the softer, more nuanced vocal passages.

Hugo Weisgall’s The Stronger (1952) was a fine compliment to the first work in dramatic structure and performance.

Drawn from August Strindberg’s short play Den starkare (1889), Richard Hart’s libretto, set in the early 1950s, tells of a chance meeting between Estelle, a former actress now married to a producer, and Lisa, her single one-time friend, at a cafe on Christmas Eve. As Estelle, insecure in her marriage, boasts of her life with her family, she grows increasingly irritated with Lisa, who sits at a table nonchalantly through the encounter unable to interject to Estelle’s accusations that she is devoid of emotion. By opera’s end, the audience is left wondering who is actually the stronger of the two women.

Soprano Janna Baty offered a strong performance as Estelle, exhibiting clear projection and diction. And in her acting, Baty exaggerated the role just enough to bring out the character’s insecurities.

Louise Hamill portrayed the silent role of Lisa with appropriate stoicism and self-assurance. Pianist Stephen Yenger did a bold job executing the musical accompaniment, which mixes polytonal and free atonal writing as it follows Estelle in her psychological crisis.

Following intermission, soprano Barbara Kilduff provided a convincing and powerful performance as the troubled Aurelia Havisham in Dominick Argento’s Miss Havisham’s Wedding Night (1978).

John Olon-Scrymgeour’s libretto, derived from Dickens’s Great Expectations, offers a more nuanced and sympathetic side to the character. Through the monologue, we see Miss Havisham relive the painful night when her fiancé jilted her at the altar. We watch her shift uneasily between reality and madness as she imagines a conversation with her former lover after so many decades. In the end, Miss Havisham, resigned to reality once again, prepares to tell young Estella all about the nature of men.

Argento, known particularly as a composer of art songs and operas, eschewed the experimental techniques that became commonplace after World War II. Like Weisgall, an early teacher of his, he employed lyrical treatment of polytonality and discreet dodecaphony for dramatic effect in a way similar to Benjamin Britten. Brian Moll, also making his Intermezzo debut, performed Argento’s score at the piano and reed organ with sensitivity.

The sets used for the performances were practical but effective (headless statue for Venus, cafe tables for The Stronger, old furniture and ready-made, smashed-looking grandfather clock for the Argento work). William Fregosi, the designer, used generous portions of red in the sets for the first two works. And the sepia tones in Miss Havisham encapsulated the character’s decaying world successfully.

Fregosi, who announced that this production would be his last with Intermezzo (though he said he will stay on in an advisory capacity), demonstrated that an opera company does not need a multi-million-dollar budget for sets in order to tell a compelling story.

“The Diva Monologues” will be repeated 4 p.m today. intermezzo-opera.org

Aaron Keebaugh has taught music history courses at North Shore Community College, Santa Fe College, and the University of Florida, where he earned his Ph.D. in musicology. He presently writes for the Revere Advocate and lives in Salem.

Posted in Performances