Knussen opera, quartet premiere headline contemporary doubleheader at Tanglewood

Oliver Knussen's "Higglety Pigglety Pop!" was performed Sunday at the Tanglewood Music Center.

A plethora of high-pitched sounds and a shaggy opera heroine seemed to announce the arrival of dog days in the Berkshires Sunday at Tanglewood.

The five-day Festival of Contemporary Music offered a chamber-music concert Sunday morning and an orchestral one that evening. Maybe it was just a coincidence, but the seven pieces in the morning program all tended to favor notes high above the musical staff, creating sonic effects ranging from ethereal to ear-splitting. It made for a concert that humans could enjoy very much, and their canine companions even more.

The high-flying trend continued with the opening work of Sunday evening’s orchestral concert, Niccoló Castiglioni’s Inverno In-Ver, a suite of pieces about winter, which evoked the season in tinkling, shimmering tones.

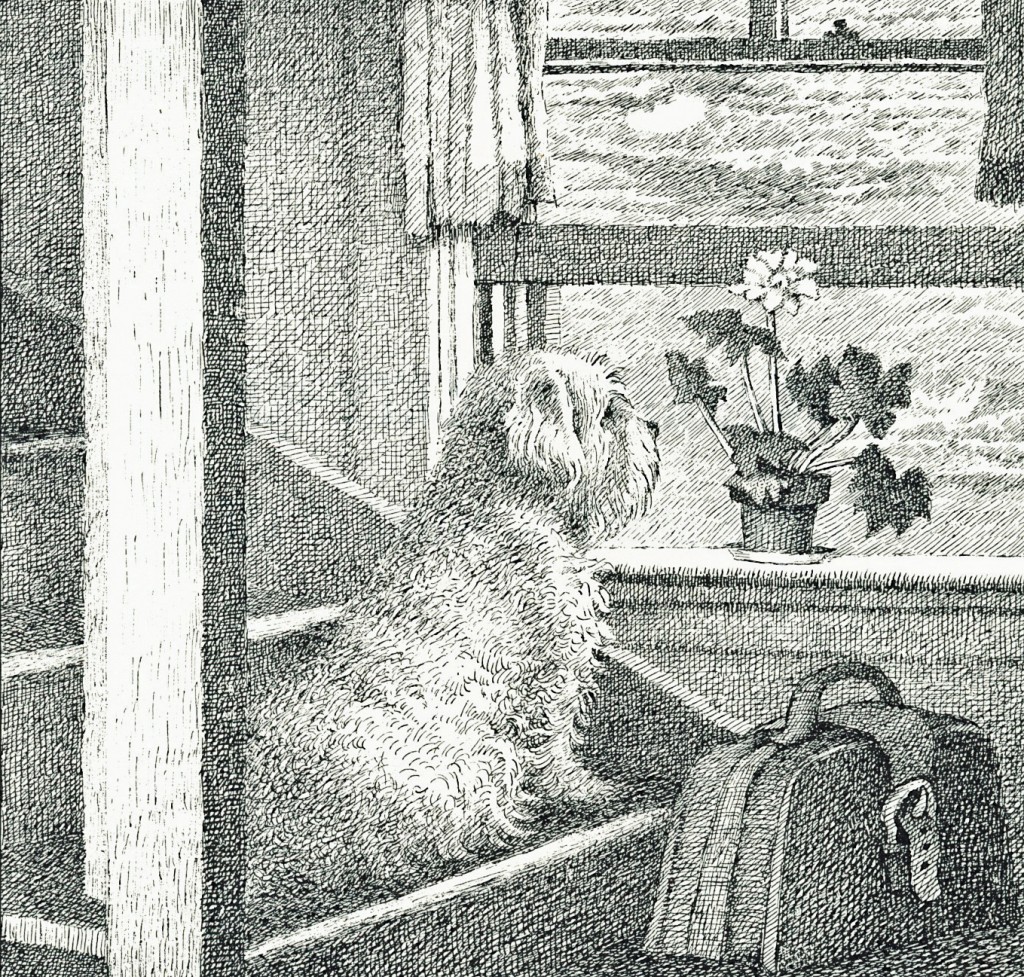

Closing the evening, Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life, a one-act opera by composer Oliver Knussen and the late author-illustrator-librettist Maurice Sendak, finally returned us to earth, in terms of pitch. It offered a different reward to visiting pooches, if any: one of their own in the lead role, a Sealyham Terrier named Jennie, ably impersonated (incaninated?) by human soprano Kate Jackman.

Headlining the morning program was a world premiere, Marti Epstein’s Hidden Flowers for string quartet, commissioned by the Tanglewood Music Center for the summer festival’s 75th anniversary. Deriving its title and inspiration from No. XVII of Pablo Neruda’s 100 Love Sonnets, the one-movement piece evoked the poet’s sublimated sensuality with glimmering sound that continually reached upward.

Abundant use of harmonics and ponticello bowing generated a sublime haze of high overtones. The piece closed with a long section of quiet chords separated by enormous silences (a typical one clocked in at 13 seconds) that seemingly invited the listener to pause and savor every sound. Epstein’s elusive music asked a lot of the audience, but in turn offered plenty to reflect on.

Besides the Epstein, the chamber program offered a satisfying variety of moods and performing forces. Dinah and Nick’s Love Song, a 1970 wedding-present piece by Harrison Birtwistle for harp and three identical melody instruments (oboes in this performance), opened the program with haunting atonal atmospherics, like a distantly recalled Elizabethan lute song. The harp at center stage and the three oboists arrayed around Ozawa Hall intertwined their sound at close intervals, making the air vibrate with acoustic beats and overtones.

The Italian modernist Castiglioni (1932-1996) has been represented on several programs in this series, including Sunday morning with Tropi (Tropes) for a sextet of winds, strings, percussion and piano. The 1959 piece in one movement, the ensemble of which resembles that of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, deals in chirpy, scurrying high phrases and sudden silences, which eventually give way to long, attenuated chords.

George Benjamin’s Piano Figures of 2004, ten pieces of only moderate technical difficulty but considerable subtlety and charm, seemed to take more after Debussy than Bartók in style, at least as deftly rendered by Ryan MacEvoy McCullough.

Billed as David del Tredici’s first composition, Soliloquy for piano found the budding virtuoso trying his hand at the atonal language fashionable in 1959, but — unsurprisingly, from what we know of the neo-Romantic to come —unable to resist the Lisztian gesture. Pianist Alexander Bernstein negotiated this challenging set of variations with flair.

Helen Grime’s Seven Pierrot Miniatures, composed in 2010 for the ensemble of Schoenberg’s classic (minus the singer), vividly characterized the sad and manic sides of the famous clown, evoking the latter with piercing shrieks in piccolo and clarinet.

While speaking a contemporary harmonic language, Sean Shepherd’s Quartet for Oboe and Strings reverted to Classical chamber-music style in its identifiable themes, lively dialogue among the instruments, and four movement-like sections. A team player most of the way, the oboe emerged with a long solo cadenza at mid-piece and some Pierrot-like scampering near the end.

A large cast of skillful and imaginative young musicians, most of them members of the foundation-supported New Fromm Players program at Tanglewood, ably served this varied menu of contemporary music.

To lead off the evening concert with an Italian composer’s “musical poems” to winter brings thoughts of Vivaldi, with whom Castiglioni evidently shared a delight in orchestral color and effects. The eleven brief movements of Inverno In-Ver, however, put the emphasis on nature imagery rather than human activities, which means much rendering of whistling winds, frosty tracery, and tinkling icicles in high metallic percussion, celesta, and string harmonics. A couple of dances were accompanied by jangly percussion, almost like a Chinese opera. Even the two movements titled “Dirge” seemed to float high in the icy sky. Conductor Oliver Knussen and his chamber orchestra achieved a remarkable range of color and expression with this frosty palette.

Illustration: Maurice Sendak

Knussen did not lead his own opera, but turned the baton over to Stefan Asbury, who made the most of Knussen’s full-bore, dramatic scoring—quite a relief to the ear after a day of so much high, attenuated sound. Sendak’s classic story, originally written and illustrated by him in book form, follows the adventures of Jennie the dog, as she sets out in search of “more to life” and encounters a pig, a cat, a housemaid, a baby, and a lion, often at some danger to herself, all in a quest to become the leading lady of The World Mother Goose Theatre. Everything that happens is perfectly logical—if you’re a seven-year-old kid.

In the libretto, Sendak kept all the zany dialogue and recast his prose narrative as rhyming verse. For his part, Knussen responded to every absurd situation with the appropriate orchestral sound or harmonic twist. The human qualities of the story that have made it a classic—the longing, fears and ironies that accompany life at any age—shone through the musical adaptation as well.

Written to be fully staged, the opera was presented here in costume with just a bit of blocking. Filling in the stage action, on a large screen above the stage, was Netia Jones’s droll, jumpy animation based on Sendak’s wonderfully detailed book illustrations.

The singers were miked to compete with Knussen’s robust orchestra behind them. As the Alice-like character at the center of all the action, soprano Jackman was winningly wily and dauntless, and in good voice. Other vocal and acting standouts in the cast included bass-baritone Richard Ollarsaba, all booming menace as the Lion (no coward he), and soprano Sharon Harms in a double turn as Rhoda the sarcastic maid and as Baby’s clueless mom on the phone. As Baby, soprano Ilana Zarankin delivered the immortal line “NO EAT!” in a shriek that put one in mind of music heard earlier in the day.

The BSO performs Copland, Barber and Beethoven under Bramwell Tovey at Tanglewood 8:30 Friday and Beethoven and Bartók under Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos 2:30 p.m. Sunday. tanglewood.org; 413-637-1600.

Posted in Performances