“Heloise and Abelard” proves uneven yet compelling in its world premiere

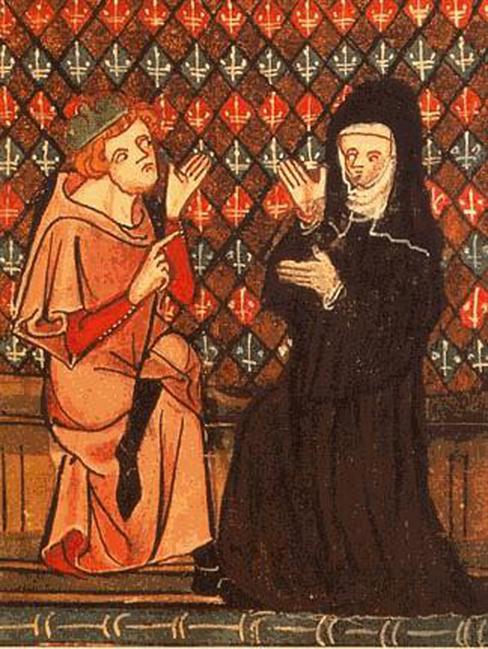

The story of Heloise (1095-1164) and Abelard (1079-1142) quickly became legendary, the tragic couple a favorite subject for writers for centuries.

The latest version, a lyric drama with music by John Austin and libretto by Christine Froula, had its world premiere Sunday in the Memorial Church at Harvard University.

As conceived by Froula and Austin and presented by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Heloise and Abelard is as much about the ill-fated love between the philosopher and his brilliant female pupil as it is about their doomed struggle against religious leaders of the epoch, here embodied by the dogmatic Abbot Bernard and greedy Abbot Suger.

Yet while bolstered by often striking musical ideas and committed performances by soloists Heloise and Abelard falters due to an uneven structure and patchy libretto.

Abelard’s intellect and his attractiveness for Heloise are unconvincing. The long and crucial scene that precipitates Abelard and Heloise’s romance consists of ambiguous pseudo-philosophical dialogue and equally ambiguous music.

Are ideas, then, supposed to be the underpinning of their romance? If so, why would Heloise remain in love after Abelard disavows her beliefs, once he discovers her pregnancy, and forces her to act against her will and conscience? And is Abelard’s mish-mash of Plato and Wittgenstein supposed to be intellectually revolutionary? Fortunately, the opera moves on, in Act 2, to the consequences of their relationship, and Austin’s music becomes more natural and convincing.

Austin’s musical language for Heloise and Abelard is thoroughly contemporary, with luscious dissonances and bold superimpositions. Medieval musical language, such as plainchants, make brief but striking appearances.

Unlike the lackluster music for Heloise and Abelard’s passion, Austin’s writing for darker emotions is both imaginative and expressive. In one memorable moment, suspicions of the lovers’ covert relationship are conveyed through a syncopated spoken chorus ending on a silibants; in another example, a scene that is almost in the tradition of bel canto mad scenes, Abelard’s off-stage voice is brilliantly underscored by a quiet snare drum. Despair is also vividly illustrated, particularly in Heloise’s mournful duet with the cello towards the end of the second act.

Less successful is Austin’s choice to alternate singing with spoken dialogue, which forces his singers to declaim over an unrelenting musical accompaniment. In fact, it is often the most dramatic situations, with the strongest orchestral component, that are consigned to speech.

Declamation aside, performances were strong all around. Tony Arnold’s Heloise was an impressive and inspiring standout. Her soprano was bright, expressive, beautifully controlled, and capable of encompassing the fearsome range Austin demands. Cleanly attacked high notes alternated with dusky chest notes, diction staying crisp throughout. Moreover, Arnold is the kind of artist whose face, as much as her voice and musicality, movingly conveys the score’s drama.

Matthew Anderson’s Abelard was not at the same level. Though his voice was generally full and warm, high notes were unsure and dry. Despite expressive singing, Anderson fails to convince that his Abelard is deeply in love with Heloise or suffering from romantic separation, castration, and religious persecution.

Jonathan Roberts, as Fulbert, sang and declaimed with verve. Paul Guttry and Charles Blandy in the roles of the abbots had full and focused voices and sang convincingly. In particular, Blandy’s excursions into head voice were an interesting metaphor for his character’s avarice.

The comprimario parts were taken by Harvard alumni; of note were tenor Jonas Budris’s incredible squillo, and Bridget Haile’s resonant mezzo-soprano. Her a cappella duets with Arnold in the second act were highlights of the opera. The Harvard University Choir sang with discipline and sensitivity, and Edward Jones conducted with care.

Posted in Performances