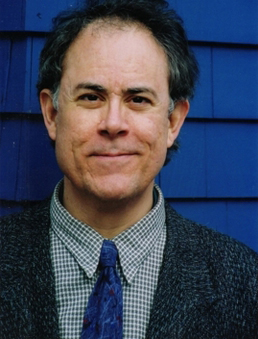

Pianist Rangell shows taste and subtle artistry in Tufts recital

Pianist Andrew Rangell performed a wide-ranging recital Sunday afternoon at Tufts University.

At one extreme, the piano recital can be a high profile, cannily marketed event featuring a glitzy star playing a program with a climactic, tumultuous conclusion.

At the other, there are programs like Andrew Rangell’s concert in Distler Performance Hall at Tufts University on Sunday afternoon. With eclectic works that complement each other, in the hands of a cerebral artist who had explored their musical meaning and wanted to share it, performances like Rangell’s may not pack halls and fill the air with apocalyptic applause.

But they offer their own considerable rewards. Rangell played works from a broad historical range, spanning from the 16th century to today, woven together with insight and eloquence.

The pianist has given only sporadic concerts in the past two decades due to focal dystonia, in his right hand particularly. He has not, however, altered his busy recording schedule, and his rich catalog on Bridge and Dorian are evidence of his taste and skill. Those who are familiar with his scholarly but non-stuffy approach know to keep an eye out for those rare performances.

Rangell began with William Tisdall’s Pavana chromatica, subtitled “Mrs. Katherin Tregian’s Paven,” an early work for the virginal (harpsichord predecessor). As the title suggests, the piece is an extended chromatic dance, with measured rhythms and elegant keyboard runs, and set the tone for the more substantial Fantasia and Fugue in C major (K. 394) from Mozart. Linked together, the two works showed keyboard exploration of straightforward development segueing into one with a more complicated structure.

A brief pause led to Carl Nielsen’s Three Piano Pieces, Op. 59. Each miniature seemed only to hint at structure, before breaking it down. In the hands of lesser interpreters, this could be a frustration; with Rangell’s insight, a sense of musical freedom prevailed.

Three sets of theme and variants followed, by Thomas Tomkins, the contemporary composer Matan Porat, and Beethoven. Tomkins’ Barafostus’ Dreame was straightforward with an elegant theme, and variations that cleverly enhanced that motif. Porat’s Variations was more esoteric, inverting a subject rhythmically and melodically, and introducing extra-musical devices like damping strings and tapping the piano.

Rangell pointed out that Beethoven’s Variations in F major, Op. 34, has the unusual progression of changing keys in a cycle of thirds. The work takes a stately, almost martial theme and instead of diverting from it, explores it more deeply. Rangell managed to vivify the structure of all three composers’ works with differing sensibilities: a sense of wonder for Tomkins, articulation for Porat’s more thorny work, and grandeur for Beethoven.

Four wildly varied works by Chopin comprised the second half of the recital. No performance is technically flawless, but loving explorations by this serious artist made up for any shortcomings. Of the set — Polonaise-fantasie, C-sharp minor Prelude, a Nocturne from Op. 62, and the unusual Bolero — the Nocturne carried the most emotional weight, but all four were played with aplomb.

A single encore continued the dominant mood of the afternoon — structured, yet not flashy — with a selection from Bach’s Art of the Fugue.

Sunday’s concert, along with other recent Tufts University events — including a sold-out performance by soprano Dawn Upshaw last month — seems to be an effort by the school to create a higher profile for its music series.

Posted in Performances