A gifted young cellist and rough-edged Bruckner with the Boston Civic Symphony

For lovers of Bruckner’s symphonies, the past few months have seen rich and invigorating performances. In February, Andris Nelsons led the Boston Symphony Orchestra in a spiritually moving rendition of the Symphony No. 9. And earlier this month, Richard Pittman and the New England Philharmonic presented a new edition of the Symphony No. 3, complete with thirty-eight measures the composer had cut from the score in 1877. Both performances were revelatory in their own way.

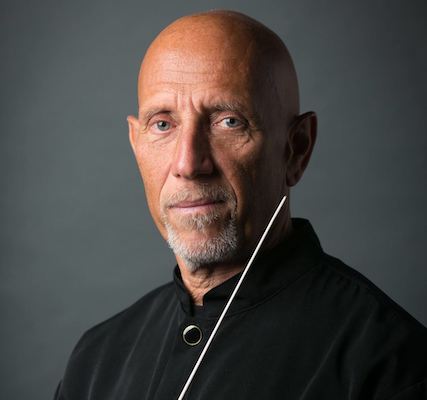

Less so was the Boston Civic Symphony’s reading of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 4, led by Francisco Noya Sunday afternoon at Jordan Hall, which proved decidedly mixed.

Though it retains much of the Wagnerian grandeur explored in the Third Symphony, Bruckner’s Fourth is shot through with an almost Schubertian finesse and fluency. For much of its 70-minute length, strings and winds engage in burbling, chamber-like passages that reflect an early-nineteenth-century affinity for nature. Bruckner, it seemed, was looking to the past with a work he subtitled the “Romantic.”

Because of its delicacy, the symphony poses difficulties for any ensemble. Noya drew attention to the many details of the score, but the orchestra unfortunately failed to bring those intimate sections into requisite focus.

Several cracked notes marred the opening French horn call, and later statements of the theme, played by the full section, fitfully stuck out of the orchestral texture. The second theme of the first movement was muddy and aimless, the strings and winds seeming to compete with one another for supremacy rather than settling into a gentle flow. Only in the tutti sections of the movement did the orchestra find something of Bruckner’s majesty and abiding mystery.

But the performance grew stronger as it unfolded, and Bruckner’s many diversions made for tasteful complements. The opening string lines of the Adagio carried both subtlety and intensity. French horns and woodwinds provided elegant countermelodies to make the music flower beautifully. The brass section put across the bold fanfares of the third movement with robust authority, and the Trio’s ländler took on rustic vitality in the strings and woodwinds.

In the finale, Noya revealed Bruckner’s grand architecture by building the long phrases into powerful statements that released the tension of the previous movements. Though marked by some unsteady moments, Sunday’s performance ultimately yielded its musical rewards.

The first half of the concert was dedicated to Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

Completed in 1919, the Cello Concerto stands as Elgar’s last significant score. With it he turned away from the Lisztian exuberance and Edwardian pomp of his Violin Concerto and First Symphony and toward a more deeply melancholic style, which the afternoon’s soloist, Brannon Cho, rendered to stirring effect.

The 25-year-old cellist’s burnished tone, spellbinding technique, and probing musical mind have won him accolades, including top honors at the 6th International Paulo Cello Competition.

Playing with verve, tasteful dynamic shading, and a keen sense of Elgar’s musical line, Cho found all sides of this affecting composition. Perfectly tuned double stops added depth to his lyrical phrases, and the passages that carried his fingers high onto the fingerboard managed to sound with dramatic weight.

Cho tossed off the agitated theme of the second movement with abandon to make this music briefly into a showpiece. But Elgar’s score is ultimately one of tender expression, and Cho colored and varied his tone to imbue the melody of the third movement with a palpable sense of longing. He carried the emotional tension into the finale, where, with mahogany tone, he laid bare the pent-up sadness etched into the soaring melodies.

Noya sensitively charted the streams and eddies of Elgar’s accompaniment. His sudden gestures teased out bright chords from the brass, while gentle arm movements shaped the string phrases with graceful flow. Throughout, the orchestra played with commitment.

Called back several times, Cho offered a vibrant performance of the Marcia from Britten’s Cello Suite, Op. 72 as an encore.

The opener, Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question, brought uneasy peace.

Under the guide of guest conductor Matthew Scinto, the musicians vividly conveyed the sublimity of this short, though famous transcendental score. The string harmonies seemed to flicker like distant starlight. From offstage, the solo trumpet posed its question with quiet presence, to which woodwinds answered with piercing dissonances and chattering figures. After the final strains faded into whispers, the ensuing silence hung eerily in the air. The universe, for Ives, offered neither hope nor solace.

Francisco Noya will lead the Boston Civic Symphony in music by Bernstein, Stravinsky, and concerto movements by Beethoven and Mendelssohn featuring the winners of the annual concerto competition 2 p.m. May 5 at Jordan Hall. bostoncivicsymphony.org

Posted in Performances