BLO scores a success with brightly colored, ’50s take on Stravinsky’s “Rake’s Progress”

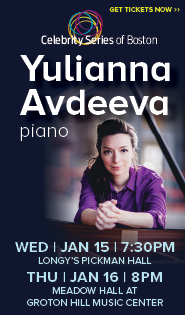

Ben Bliss as Tom Rakewell and Jane Eaglen as Mother Goose in Boston Lyric Opera’s production of Stravinsky’s “The Rake’s Progress.” Photo: T. Charles Erickson

At a Chicago exhibition in 1947, Igor Stravinsky saw paintings and engravings by 18th-century artist William Hogarth that traced the downward journey of a man from simple country life to city debauchery. The story fueled the composer’s imagination for The Rake’s Progress, his most popular opera and his last work of churning neoclassicism.

Its story turns the narrative of Christian pilgrimage on its head. Tom Rakewell forsakes his beloved Anne Trulove to follow the cunning Nick Shadow, who is actually the Devil, into London, where he is consumed by gambling, prostitution, and other worldly pleasures. Anne, ever devout, comes to Tom by work’s end. It is, though, too late for him, and he dies after spending his remaining days in Bedlam, London’s insane asylum. The moral of this opera, stated in the epilogue, recasts Puritan ideology for the ages: Idle hands are the Devil’s playthings.

The Rake’s Progress opened at the Cutler Majestic Theatre Sunday afternoon in a new production by the Boston Lyric Opera. Darkly psychological, delightfully absurdist, and warmly humane by turns, the performance stands as a highlight of the current music season.

An interesting addition to director Allegra Libonati’s production is the inclusion of Stravinsky himself. The opera opened with the composer gazing at the Hogarth paintings and then, as if transfixed, he begins air conducting. The piece unfolds as if in his imagination.

The composer, played convincingly by Yury Yanowsky, is for the most part a silent presence onstage. Sometimes he sits or stands and watches the scenes unfold, with his air conducting occasionally giving him something to do. But as the story unfolds, Stravinsky is drawn into a battle over Tom with Nick Shadow, the only other character with which the composer interacts.

The maximalist set designs effectively capture 1950’s clichés and abstracted extravagances of the city. The scenes in the country employ backdrops of row houses in forced perspective. Trulove, Anne’s father, as in Leave it to Beaver, even mows the lawn while well dressed. The scene in the brothel was bathed in pink neon lights, Tom’s lavish apartment in gold, complete with mirrors and giant bathtub. The final scene, set in Bedlam, was chillingly conveyed through the use of the theatre’s bare rear wall, the cream-colored brick covered in aged black streaks.

The cast was consistently excellent. Tenor Ben Bliss, who has recently been awarded Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal Award, made an attractive BLO debut as Tom Rakewell. Bliss conveyed the character’s torn feelings at having abandoned Anne, at one point singing about his feelings for his forgotten love before jumping into a ménage à quatre. Bliss’ singing was warmly lyrical, his tone bright and buttery, recalling the voice of Jerry Hadley. His first Act aria “Here I stand” sounded with bold conviction. Fate, not work, would rule Tom’s destiny.

As Anne Trulove, soprano Anya Matanovic found the innocence of the girl next door. She handled the work’s punishing leaps with aplomb, delivering a searching “No word from Tom” and a vibrant and precise “I go, I go to him.”

Kevin Burdette was a smooth operator as Nick Shadow. His bass voice was clarion and penetrating. When Tom bests him in a card game, Burdette’s performance turned chilling. Stripping off his vest, shirt, and wig, he sang a terrifying “I burn, I freeze,” while rubbing blood all over himself.

Heather Johnson found the opera’s humor as the bearded lady, Baba the Turk. She made for an energetic and appropriately annoying celebrity wife to the bored Tom. When she fought him over a letter from Anne, Baba fell into the bathtub, knocking herself unconscious. She didn’t awake until the auction scene, which Johnson milked for laughs. Johnson’s mezzo-soprano is rich and dark, and she affectionately conveyed the character’s tender side in her scene with Anne.

Rounding out the cast were baritone David Cushing, who sang robustly as Trulove; celebrated soprano Jane Eaglen, who performed strongly as brothel owner Mother Goose; and tenor Jon Jurgens, who sang with sly charm as Sellem the auctioneer. The chorus, throughout, performed with energy and vitality.

Costume and set changes were often done without breaks between scenes, which kept the opera moving at a healthy pace. Jon Conklin and Neil Fortin’s costumes were simple: various shirt and pants combos for Tom, grey dress for Anne, and suit for Trulove. Tom spent much of the opera in little more than his shorts as the character engaged in his orgies and soaked in bathtubs. Sellem’s costume, tuxedo jacket revealing a bare chest, tights, high heels, and pink wig, made a standout of this minor character. Baba’s blue dress, with its silver trim and long train, was posh and effective.

The orchestra performed superbly, though at times the work missed the sparkling clarity and rhythmic precision for which it is known. But David Angus drew playing of soft intensity that highlighted the unusual warmth of Stravinsky’s score.

The Rake’s Progress runs through March 19 at the Cutler Majestic Theatre. blo.org

Posted in Performances