Performances

Pianist Fujita shows mastery, versatility in Vivo recital debut

Already established as a fine interpreter of Classical and Romantic repertoire […]

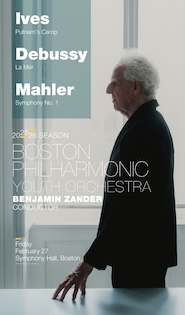

Zander leads Boston Philharmonic in stylish Mozart and noble Bruckner

One might not guess it from this weekend’s concerts at Symphony […]

Salonen returns to BSO with clarifying Bruckner and his delightful Horn Concerto

Sometimes a change of pace can be a healthy thing. Take […]

Articles

Top Ten Performances of 2025

1. Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Die tote Stadt. Andris Nelsons/Boston Symphony Orchestra […]

Concert review

Boston Cecilia celebrates 150 years in style with Bach and Handel gems

Longevity in a performing organization is often guaranteed by championing new music as much as returning with conviction to the repertoire that defines it.

Celebrating its 150th season in “A Feast of Remembrance,” Boston Cecilia, led by music director Michael Barrett, offered a program of Bach, Handel, and Purcell Sunday afternoon at Jordan Hall that grounded the milestone year firmly in Baroque works.

The afternoon was marked by elegant string shaping and a poised blend among period instruments. The Introduction of Purcell’s Hail! Bright Cecilia unfolded in stately procession, with interwoven colors from strings on the opposite side of winds and brass. The Canzona’s polyphony revealed careful balance on top of the continuo section.

The performances also showcased excellent casting of soloists, both individually and also cohesively with one another, as well as the purity of sound this ensemble cherishes. The first half centered on two Bach cantatas later incorporated into the monumental Mass in B minor: Gott, man lobet dich in der Stille, BWV 120, and Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191.

Countertenor Wee Kiat Chia delivered the opening aria to the former with silky tone and agile coloratura, though the orchestra occasionally covered his lower register. The opening chorus adopted a declamatory stance and melismatic passages aligned cleanly if a bit squarely. By contrast, the middle section’s minor-key dissonances were shaped with expressive clarity. Baritone Junhan Choi’s extended recitative unfolded with organic ease, his crisp English diction and buoyant interpretation allowing the movement gentle authority. After a brief restart in “Heil und Segen,” coordination with the violin obbligato part wavered momentarily before soprano Carley DeFranco’s entrance. Her bright, sweet timbre immediately set her apart, caressing the text with warmth and musical sensitivity. While some German consonants were softened by the instrumental texture, her communicative intent remained clear.

Baroque gestures were thoughtfully considered throughout. In the opening “Gloria in excelsis Deo,” word stresses informed melodic phrasing, though initial consonants could have carried more presence and weight. The transition to “Et in terra pax briefly” ruffled before settling into a cohesive, simple calm. The “Gloria Patri” duet for DeFranco and tenor Lawrence Jones shimmered with buoyant energy, their voices and gestures blending in sprightly figures. Though Bach’s later revisions for the B Minor Mass are often considered more complete, the original text settings here felt especially natural to the voice. This was evident in the concluding “Sicut erat in principio,” where the Boston Cecilia polished the fugue with sparkling entrances.

After intermission, Handel selections traced a loose narrative across several works. “Let their celestial concerts all unite” from Samson, HWV 57, opened with a solid, unified choral sound, voice parts cutting through cleanly while maintaining ensemble cohesion. The interaction with the trumpet figures provided a sense of symmetry to the reading.

In Judas Maccabaeus, HWV 63, warm orchestral textures evoked a gently rolling sea. Choi’s following accompagnato again showcased crisp diction, leading to a persuasive “Arm, arm ye brave!” where his admirable rendition featured trumpet-like articulation. The repeated “strengthen your hands” lines highlighted his vocal and interpretive reach: the first was a declamatory cadence in forte and the second an ornamental cadenza passage showing off his lower register. The orchestra attached to his shaping with ease and tricky unison doublings merged seamlessly.

More musically interesting Handel movements emerged in selections from Theodora, HWV 68. In “Thither let our hearts aspire,” DeFranco’s pure soprano floated and Chia’s pastel-toned countertenor blended with sensitivity, especially in tighter, more contrapuntal intervals. A soloist from the ensemble, Jamie Chelel, offered assured projection as Irene, followed by a glowing chorus “O love divine,” delivered in velvety textures of this ensemble’s signature unity.

In “Thais led the way” from Alexander’s Feast, HWV 75, DeFranco displayed a silvery timbre prized in this repertoire, paired with lively personality in little Baroque gestures. Barrett joined as recorder player while conducting the subsequent accompagnato mostly successfully, in which Chia’s smooth eggshell tones complemented gently.

The afternoon’s climax arrived in the chorus “At last divine Cecilia came,” true to the ensemble’s namesake, with their combined sound expanding luxuriously in the hall’s acoustic. Chromaticism and wide-interval leaps glided smoothly, while the continuo supplied just enough grit for quilted elegance.

Tenor Lawrence Jones shone in the aria “The enemy said” from Israel in Egypt, HWV 54, his forward-moving melismas and sequences building to exciting dramatic heights. His final cadenza showcased ease in the upper register, always maintaining consistency of his satin tone. “The Lord shall reign” allowed various chorus sections to shine in its straightforward, repeated tune, while culminating in a satisfying unison after the polyphonic “The horse and his rider” section.

The program closed with the “Dona nobis pacem” from Bach’s B Minor Mass, the chorus enveloping the hall in blended legato lines—warm, tender, and quietly hopeful.

Boston Cecilia presents “A New Song,” a program of newly commissioned pieces and recent premieres 7:30 p.m. May 16 at All Saints Parish in Brookline and 3 p.m. May 17 at Methuen Memorial Music Hall. bostoncecilia.org

Posted in Performances

No Comments

Calendar

February 26

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Thomas Adès, conductor

Augustin Hadelich, violinist […]

News

Boston Classical Review wants you!

Boston Classical Review is looking for concert reviewers based in […]