Haitink and BSO deliver rousing Mahler and elegant Beethoven

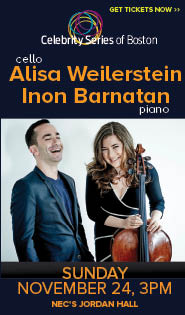

Murray Perahia performed Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4 with Bernard Haitink and the BSO Thursday night at Symphony Hall. Photo: Michael Blanchard

In the mid-1980s, pianist Murray Perahia and conductor Bernard Haitink teamed up to record Beethoven’s piano concertos with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. The resulting discs, released on the CBS Masterworks label, showcased playing of live-wire intensity and revealed Perahia as a major force in Beethoven performances on the same rarified level as Claudio Arrau and Alfred Brendel.

Thursday night at Symphony Hall, Haitink and Perahia were reunited in a performance of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Beethoven’s ebullient concerto is noted for its sunlit lines and expansive form. The pianist, in an unusual move for the time, opens the concerto with soft chords that are picked up by the strings.

Perahia played with a sparkling technique and a touch that had a distinctive weight. Each note rang clear, sounding with a ping. His command of the piece’s filigree was excellent, and he played the runs with crystalline precision, his statements taking on a particular fury in the outer movements. Perahia also rendered the softer sides of the music with golden touch, as evidenced in his silky smooth performance of the first movement’s broad themes.

His most affecting playing came in the second movement, where he supplied a spacious and searching touch to the musical line in answer to the strings’ stark, angular statements. The finale moved with a dance-like energy, with Perahia playing the difficult runs with dexterity.

Haitink led an accompaniment of soft elegance, the movements unfolding in grand arcs of sound. Throughout, the orchestra responded with plush tone. The only quibbles came in the soft statements of the finale, which lacked rhythmic precision.

Those issues were remedied in the concert’s second half, which brought a vivid performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. This week’s concerts celebrate the 45th anniversary of Haitink’s first appearance with the Boston Symphony.

The BSO’s conductor emeritus led the First Symphony in broad strokes without losing sight of the details embedded in the composer’s hour-length score. Tempos were solid and deliberate, and Haitink took care to build the drama as the piece progressed. Each statement fell neatly into place.

The opening statements of the symphony seemed to rise from the mist, with winds sounding out bare intervals from the unwavering A spread out over several octaves. Haitink conducted the movement in a stately tempo, emphasizing the Schleppend (“dragging”) of the marked Langsam. The music didn’t lack for energy as the quotation from Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer still managed to sound with a joyful lilt.

The second movement Ländler moved with a sure-footed feel, and the restatement of the principal theme, after the sensitively played trio, took on a boastful air in its quicker tempos.

The funeral march of the third movement moved with a subtle urgency as the fugue on the familiar Frère Jacques theme emerged from bassist Ed Barker’s silvery solo. The ensuing passage, with its klezmer overtones, had a wry humor, and the music central to the movement featured sunny contributions from violins and winds.

Brass and percussion laid on the thunder for the finale, and horns and trumpets supplied a sturdy wall of sound. The large horn section required for this work stood, as marked in the score, for the final statement, which brought the symphony and the concert to a rousing conclusion.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday, Saturday, and Tuesday at Symphony Hall. bso.org; 888-266-1200.

Posted in Performances

Posted Apr 03, 2016 at 6:04 pm by Allan Kohrman

I heard Haitink conduct the Mahler 1st in Amsterdam in 1968. 48 years ago! The whole thing is rather daunting.

Posted Apr 06, 2016 at 8:56 am by Thomas

I listened on Tuesday night. By the fourth performance, the symphony from start to finish was new in Haitink’s hands. He brought out the symphony’s origin as an amalgam of songs, a tone poem for symphony. This was clear to me from the first presentation by the cello section of the opening theme (meaning I caught on at that point). The songs were made present in crystal clear melodies, accompaniments, and polyphony where in the third movement the second presentation of klezmer dances above frere Jacques.

This work was built out by Mahler over more than 10 years, evolving from song and poem to a symphony bent on dragging from the cold, still hearts of Imperial Europe a felt experience of death and rebirth. Haitink brought the symphony’s origin in songs back to the fore and for this the audiences and, importantly, players followed the performance by flipping out with gratitude. It was a great night for BSO.